|

Marjorie Otto, Beloved Community Communications Team One of the blessings of our Unity Church community is the number of people that call it a spiritual home. With so many individuals that make up our community, it can also make it hard to get to know everyone at the depth we crave here in our work at Unity. As a way to create a tapestry of Unity voices, the Beloved Community Staff Team, aided by the Beloved Community Communications Team, is starting a new project within the congregation called, “All Our Fullness.”

The goal of the project is to provide a way for congregants to introduce themselves in a personal way. Here’s how to participate:

The idea for the project and its name is pulled from the fourth of the Unity Church ends statements, which guide our work, “Know each other in all our fullness and create an ever-widening circle of belonging for all people.” We hope this project can serve as a starting point for deeper relationships among us. We also hope to create a tapestry, a sampling, a “Unity community quilt” of sorts, of the folks that make up the Beloved Community here. For this introduction of All Our Fullness, here is the inaugural question and prompt: What illuminates your commitment to creating an antiracist multicultural community? Share a story, image, and/or video. This is just the very beginning of this project. We’re exploring many ideas, avenues, and directions for how this project may evolve over time, so we’re leaving the future of it open-ended to make space for its growth. Look for more information in upcoming newsletters and a future table in Parish Hall, as this project grows. The evolution is also going to depend on the level of participation, meaning you, yes, you dear reader, are the perfect person to submit a response. Submit to All Our Fullness!

0 Comments

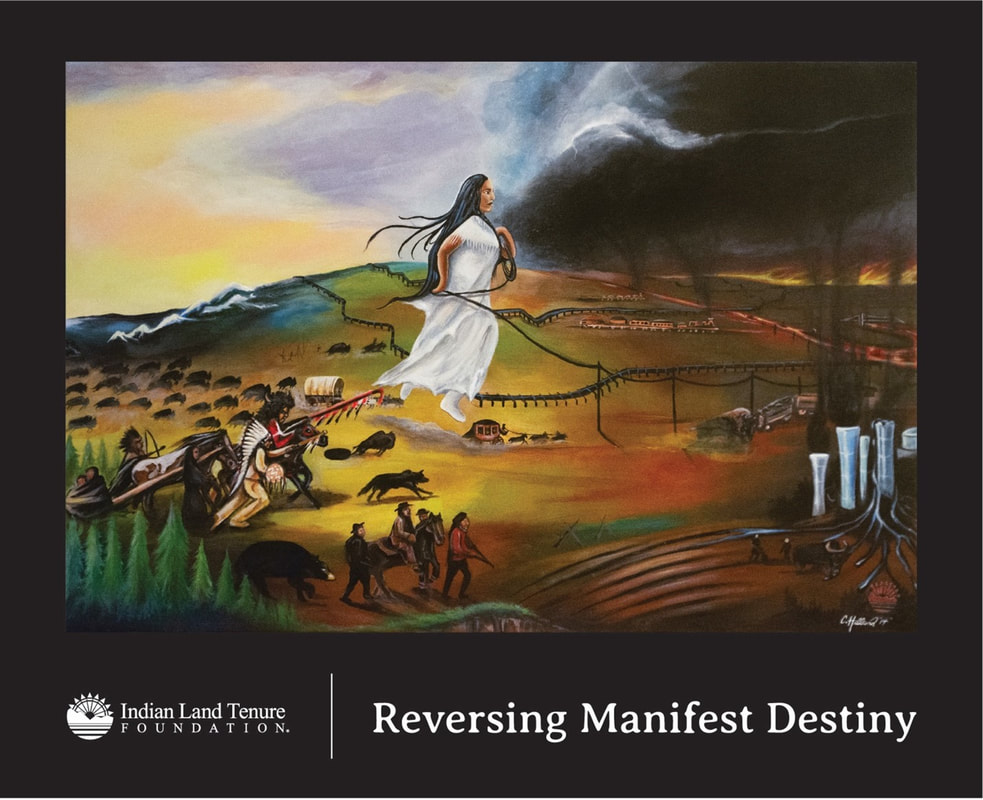

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team I believe stories change hearts and minds, and we are in such civic and social conflict that we need stories that help create conditions of possibility for social healing…. When we lead with our heart, we learn that our mind and body more closely align with putting thought into action. In short, faith without works is dead. Faith, being that thing that animates our heart, our internal narrative of how we make sense in this vast world, is compelled by the questions of what and how: What do we do? How do we do it? These two questions—what do we do and how do we do it?—are central to the conversation surrounding reparations to Indigenous communities and nations for treaties broken and land stolen. Several years ago when members of Unity Church-Unitarian began a conversation with Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Mohican) of Healing Minnesota Stories about efforts to restore and maintain Indigenous language, culture, and land, the idea of “land back” remained elusive, something we would figure out years from now. However, today reparations can take on many forms well beyond the singular view of returning the land on which Unity sits to a Dakota community and leasing it from them. Before any final solution to American history can occur, reconciliation must be effected between the spiritual owner of the land—American Indians—and the political owner of the land—American Whites.” The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery and its Repair Network are spearheading efforts to pass a surtax on Minnesota real estate sales to support Indian programs run by Indian people. The proposal is called the Indian Recovery Act or IRA. Here is an overview of the plan to be introduced during Minnesota’s 2025 legislative session:

This proposal is the culmination of work by Dakota and Ojibwe tribal councils and their allies. Originally intended to be introduced during the 2024 Minnesota legislative session, the parties involved determined the original bill needed some tweaking, and would fare better during a non-election year. The delay gives us extra time to help build support for the IRA. For additional information, contact the Repair Network’s Legislative Team at [email protected] or call 612-440-4526. They are looking for volunteers to speak at churches and other faith communities, write letters of support, testify before legislative committees (when the time comes), and other tasks that will move the IRA forward. As Che-Espinoza, one of my pillars of spiritual foundation, writes: Heart work demands attention to one’s own complexity and the narrative that we live with, day in and day out…The mind is a valuable tool for our becoming activist theologians, but the heart and the ability to (em)body our feelings generate the most robust action and help tie together thinking with action. The heart of becoming is in finding the plumb line of one’s own story. That’s the heart of activist theology. Marjorie Otto, Beloved Community Communications Team I think it’s safe to make the generalization that for many of us who find ourselves in a liberal theological community, one of the most difficult tasks asked of us is to develop a spiritual practice. And don’t even get me started on my (and probably others’) struggle with developing a prayer practice; that’s for another newsletter. Thankfully, we find ourselves here at Unity Church with a plethora of circles, sources, events, and publications to support that task. But even with all those resources, the learning never stops, so I joined the late-February follow-up to the fall 2023 series Spiritual Practice: Discovery and Transformation, with Rev. KP Hong to continue my dive into spiritual practice. If you are contemplating these questions, you are not alone:

It can be overwhelming to know what a practice can look like that fulfills within, among, and beyond needs. During the February event, KP reminded us of the core definition of spiritual practice: it’s how we connect to the whole, the holy, that which is greater than the self and greater than the ego. He also reminded us of the unbreakable bond between spiritual practice and antiracist practice. We cannot think to dismantle racism without the transformation a spiritual practice provides to us to connect to that which is greater. This intertwining is seen in the Double Helix Model in which spirituality and antiracist work at the within, among, and beyond levels to break down white supremacy. We were asked to consider these questions as we shared what our practice looks like:

Of all my spiritual uncertainties, I’ve always known that nature has been, and always will be, my connection to that which is greater because it is the realm in which I’ve experienced the most awe: the pulsating of an aurora borealis, waves lapping against rocks, and a Cooper’s Hawk raising its young in our backyard silver maple. A spiritual practice for me is anything that brings me outside.

We were then asked to name our antiracism practice and to look at how it and our spiritual practice come together to support each other. And if it was hard to name how the two support each other, are there adjustments to be made to increase that support? That’s where I find myself: ruminating on the adjustments. I feel a connection between my roots in nature and an antiracist practice of acknowledging how environmental destruction is a white dominate act. However, I don’t yet know how to clearly define that thread to someone else. This idea of spiritual and antiracism practices supporting one another follows a theme. The disconnections we often experience in our capitalist society that does not value spirituality, rest, community, art, face-to-face communication, or humanity as a part of nature, lead to other-ing and barriers. We put up barriers thinking that we need protection between the “other” and the “self.” Within the “self,” even more barriers go up to create separations of the body, the mind, the persona, and the ego. When all these barriers become impermeable, it easy is for us to see ourselves as separate from the “other.” That’s how we find ourselves in these problems: racism, environmental destruction, individualism, and burnout. If we are unable to move through these boundaries to see ourselves as connected to the “other,” the disconnection leads us to see a race different and as less-than. It leads us to see humans as having dominium over nature rather than as a part of it. Disconnection ends in destruction. But spiritual practice is the key to rebuilding those connections. Maybe you’re thinking that seems a bit overblown: “My spiritual practice can’t really hold that much weight; all I’m doing is going for a walk or sitting on a meditation cushion.” That’s where the February event culminated: not only should your spiritual practice be about the space to transform the self, the within, it should serve to transform the other, the beyond. The final question hints at that: Does your spiritual practice bring you comfort, or does it bring you to connections you’re uncomfortable with? The call to action is the answer you and I are trying to find: If your spiritual practice pushes you to connect with something you’d rather avoid, to discomfort, that is your spiritual practice. |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

July 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |