|

Maura Williams, guest writer for the Beloved Community Communications Team Member of the Racial and Restorative Justice, Artist in Residence, and Art Teams  Fourteen inmates of the Minnesota Correctional Facility–Shakopee, the only women’s prison in Minnesota, enter the group room for a Restorative Justice Healing Circle. This will be their routine for the next ten Thursdays. The women, though dressed alike in gray sweatpants and sweatshirts, represent different ages, backgrounds, races, crimes and sentences. Each takes a chair in the circle, uncertain what this experience, for which they signed up, will require of them. I take roll and send the attendance sheet to the control desk. We talk about Restorative Justice (RJ) and the Circle process; about providing a respectful place to center on accountability and healing. And how, in contrast to the punitive consequences assigned by our criminal justice system, RJ seeks to restore wholeness to all impacted by a crime: victims and perpetrators and the broader community. My co-facilitator and I lay out expectations. This entire series will be conversation, we say. We then discuss as a group what values we wish to honor and uphold during our time together. Words like courage, honesty, respect, compassion are offered. There is coherence between the physical setup of the Circle, the quality of conversation that ensues, and building trust:

I think of Circle as a non-white-centered way for people, both known and strangers, to engage in a slower, more attentive way to be together, in which we focus on who someone is rather than what they do. We remind the women that they are not their crimes, and then we ask them to tell their stories. All in the group feel respected and safe and, over time, the group becomes non-judgmental in their listening. When I think of my own experience of meetings, I am reminded of how dominant culture seems to be driven by productivity:

Some have felt that the Circle process has at times been misappropriated when adapted to meet white cultural patterns. This happens when getting the work done supersedes relational values. See “White Supremacy Culture Characteristics” by Tema Okun for more on this. I learned the Peacemaking Circle process from members of the Inland Tlingit Nation of Yukon Territory, Canada, who have been sharing “community-based justice” for years. Circle Keeper training confounded me at first. I had expected to be instructed on facilitation techniques, but training consisted of days of sitting in Circle, listening to people respond to questions about life experiences, personal challenges and aspirations, or just what was on their hearts. We were being trained to listen. Circles are used in a variety of situations from school to organizational settings, providing a respectful space to resolve conflict, determine appropriate amends, talk about wrongdoing, and to deepen relationships among people of differing backgrounds and experience. For example, I recently served as a Circle Keeper for Museums Advancing Racial Justice hosted at the Science Museum of Minnesota, with the Smithsonian. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) professionals from around the country attended, and I learned this can be lonely work. At the beginning and end of each of the three days, participants attended circles to deepen their experience and new relationships, that will support their important work.

I used to think that ending racism requires us all to interact more with people that don’t look like us, in order to dispel the knee-jerk racist perception of those people as “other.” This still seems true, but it is how we interact with people, no matter their race, that is critical. Recognizing that there is something to learn from other cultures about how to be together can catalyze the shift we yearn for towards Beloved Community.

Our Healing Circles at MCF-Shakopee are consistently comprised of mostly white inmates, and is demographically more in line with the state population, unlike men’s prisons. Written evaluations at the end of the series include statements like: I feel better about myself; like I am willing to move on, and let go of what landed me here in prison. I owned my part even though I didn’t want to. I am compassionate with peers because I recognize that it isn’t what’s wrong with her but more what has happened to her to get such action. We never know if there are happy endings for the women we get to know. Though they speak of change and creating better futures for their kids, some return to the same neighborhoods, relationships, and lifestyles where old expectations do not support fresh beginnings. But most are resilient and resourceful survivors, empowered by the unique bond of Circle. They have laughed and cried together. They have seen themselves in each other’s stories and have been there for each other. I hope that this experience will help each woman pursue the long process of healing and forgiving herself; that she will hold in her heart the group of exceptional women who listened to her story attentively and respectfully, and that she will continue to source in herself the strength to speak her truth bravely.

0 Comments

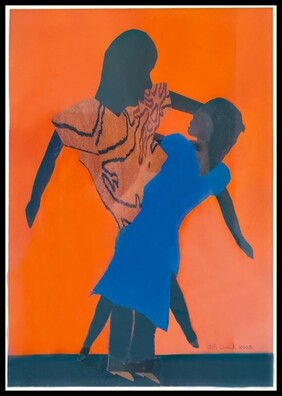

Paul Rogne, Guest Writer from Unity's Art Team  In November 2023, the Unity Church Art Team featured a Parish Hall exhibit of artwork by Rose and Melvin Smith, esteemed elders in the African American artist community of the Twin Cities. It was the culmination of a journey that began in 2021 when the art team sought these artists out hoping to purchase one of their paintings. After visiting with the art team and touring Unity to see the permanent art collection, Rose and Melvin agreed to sell one of Rose’s fine paintings, an image of a woman she met in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. That painting now hangs in the Center Room. The Smiths told us they were impressed with Unity and wanted to thank our church community for its commitment to promoting the arts. Their interest and ours resulted in an exhibition of their most recent work, none of which had ever been shown. Over the years, the artist couple has exhibited several times in New York City; their works depicting scenes and impressions of life in the history of the Rondo neighborhood are currently being featured in a Manhattan gallery. They have also exhibited in Chicago, Oklahoma, and at the Weisman Museum in Minneapolis. It has been a privilege to have them exhibit new work at Unity Church. Rose’s latest is a series of canvases capturing flowers arranged in the style of the Japanese art form, Ikebana. Melvin’s colorful collages were inspired by the classical American dance form the Jitterbug. Why did the art team reach out to these particular artists? In addition to the quality of the work, the team looks to questions prompted by Unity’s Ends Statements (2018) in considering the criteria to use in selecting artists for this program:

If our ends statements plus Unity’s mission to “transformation through a free and inclusive religious community …” are to be taken seriously, then the art team is determined to move forward on them. What shows that movement up to this point? Not only have we shown and continue to invite artists of greater diversity regarding ethnicity, race, gender, culture, religion, sexual identity, socioeconomic, physical ability, and neurodiversity to participate in Unity’s monthly exhibitions but we have also expanded the church’s permanent art collection featured throughout the building to include this diversity. There are now many more artists from our greater community represented on our walls including artists of color, LGBTQ+, Hmong, Karen, and more. In 2022, Mica Lee Anders, a Rondo neighbor and accomplished artist and educator, led a group of Unity volunteers to create an eye-catching new Foote Room mural. The shape of the overall design is familiar to Unitarian Universalists — a chalice. In October 2023, the Parish Hall featured works created by artists incarcerated in Minnesota correctional facilities. These talented artists claim roots in a variety of ethnicities and cultures. Art From the Inside, the organization that brought them here, was able to hold a successful fundraiser at Unity, and was the recipient of a Sunday offering —another example of how the art team strives to act on our ends. We know there is much more to do, but it is exciting and rewarding work. The art team urges everyone at Unity Church to be curious. Take a moment to look at the artwork as you wander through the hallways or gather for a meeting. Chances are you are seeing art that represents the concerns, ideas, thoughts, and/or feelings of a member of our greater Beloved Community. That should be reason enough to take notice. Suki Sun, Beloved Community News Guest Writer, and Shelley Butler, Beloved Community News Team

Sometimes two but more often four to five people make a commitment to read, listen, or view a resource vetted by a small committee at Unity dedicated to expanding the understanding of racism for the purpose of dismantling it. The pairs or groups gather over two-three months and then come to a larger meeting to report what surprised them about what they learned, what questions arose, and what they are called to do next. This is the Unity Church Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) program, which arose out of Justice for George/Next Right Action discussions in the summer of 2020. Suki Sun is a participant in the program with a story to tell. She was born in Shanghai, China, and lived in Manhattan for ten years before moving to Minnesota two years ago. She has been involved in two ALP groups this year, and in that short time has impressed us with her dedication to the program and her wisdom. Suki’s Story Being a person of color myself doesn’t automatically make me immune from racial bias — this is the biggest lesson I have learned since joining the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners program. I learned that the hard way during a conversation at Recovery Cafe Frogtown with a recovery coach and motivational speaker who is a middle-aged African American gentleman. I mentioned to him that since I got sober, I picked up the violin again after a 30-year pause and recently joined an orchestra in Saint Paul. “Which orchestra?” I could see his interest twinkling in his eyes. “East Metro Symphony Orchestra and it used to be called 3M Symphony Orchestra,” I replied. “Oh! 3M Symphony!” Now his eyes were totally lit up, “I had been to many of their concerts before they changed the name. What a great orchestra you have joined! Congratulations!” On top of the excitement whenever I meet someone who enjoys classical music, I also noticed that this time, it included a tone of uneasy surprise, or I could even call it a mind shock based on his race; he was the first African American I ever talked with about classical music. I was struggling with some racing thoughts. I wanted to tell him how unique it was for me to talk with an African American who supports live classical music concerts, which was a fact to me, but sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. I also wanted to mention that I wish there were more African American musicians in our orchestra (we have zero), which was also a fact to me but also sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. And the loudest question echoing in my mind at that moment was, “Why do you think we don’t see more African Americans in the classical music scene?“ And of course, I didn’t say that either. My racial bias acted like an automatic yet dysfunctional machine, vacuuming the air from my mind, suffocating the natural flow of an otherwise delightful chat about classical music, one of my favorite topics. In the end, I didn’t have the mental capacity to extend and deepen our conversation about classical music by asking him, “Who are your favorite composers and conductors? What is your favorite piece? Do you play any instruments?” In the end, I was the one hurt by my racial bias because I ruined the chance to connect with another person in a more profound and meaningful way. After all, in recovery connection is the opposite of addiction. I also lost the opportunity to hear more details of his story as an avid classical music supporter to uproot my bias. New wisdom always plants more healthy seeds when we learn from a powerful story instead of abstract statements. But I didn’t value the personal stories from BIPOC as a tool to wither my racial bias until I was in the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) group this spring. In an intimate setting of five members, we listened to ten episodes of the podcast “The Sum of Us,” which included personal stories from Memphis to Orlando, from Kansas City to Manhattan Beach, California; and then met weekly to digest these stories. During our meetings, I find that as long as I keep my eyes and mind open, even just one person's story is powerful enough to change my years-long, or even decades-long wrong assumptions. That’s why I am so grateful to be part of the Antiracism Literacy Partners. Small group, small steps, but big potential. Evolution always will feel charming. Note: The League of American Orchestras, in “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Diversity in the Orchestra Field in 2023,” reports that while the U.S. Population of Blacks is 12.6%, the percentage of Black people in orchestra is only 2.4%. Read the report for their analysis and recommendations for correcting the inequities. Anyone can join Unity's Antiracism Literacy Partners program. Questions? Contact Becky Gonzalez-Campoy at [email protected]. |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

July 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |