|

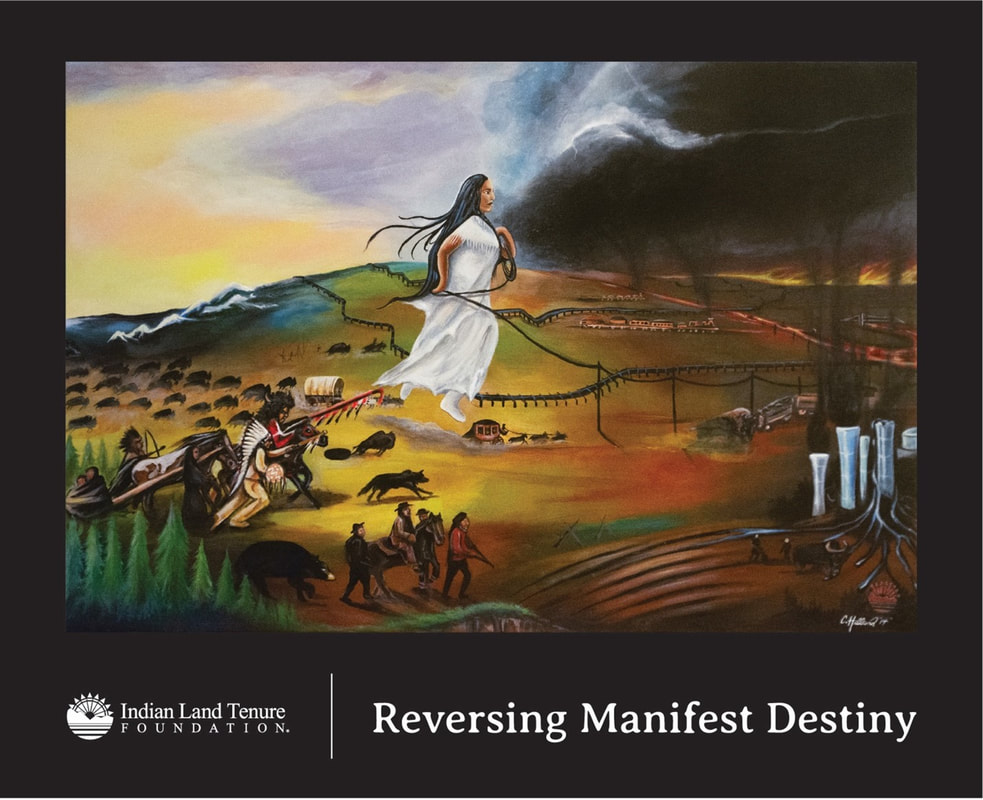

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team I believe stories change hearts and minds, and we are in such civic and social conflict that we need stories that help create conditions of possibility for social healing…. When we lead with our heart, we learn that our mind and body more closely align with putting thought into action. In short, faith without works is dead. Faith, being that thing that animates our heart, our internal narrative of how we make sense in this vast world, is compelled by the questions of what and how: What do we do? How do we do it? These two questions—what do we do and how do we do it?—are central to the conversation surrounding reparations to Indigenous communities and nations for treaties broken and land stolen. Several years ago when members of Unity Church-Unitarian began a conversation with Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Mohican) of Healing Minnesota Stories about efforts to restore and maintain Indigenous language, culture, and land, the idea of “land back” remained elusive, something we would figure out years from now. However, today reparations can take on many forms well beyond the singular view of returning the land on which Unity sits to a Dakota community and leasing it from them. Before any final solution to American history can occur, reconciliation must be effected between the spiritual owner of the land—American Indians—and the political owner of the land—American Whites.” The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery and its Repair Network are spearheading efforts to pass a surtax on Minnesota real estate sales to support Indian programs run by Indian people. The proposal is called the Indian Recovery Act or IRA. Here is an overview of the plan to be introduced during Minnesota’s 2025 legislative session:

This proposal is the culmination of work by Dakota and Ojibwe tribal councils and their allies. Originally intended to be introduced during the 2024 Minnesota legislative session, the parties involved determined the original bill needed some tweaking, and would fare better during a non-election year. The delay gives us extra time to help build support for the IRA. For additional information, contact the Repair Network’s Legislative Team at [email protected] or call 612-440-4526. They are looking for volunteers to speak at churches and other faith communities, write letters of support, testify before legislative committees (when the time comes), and other tasks that will move the IRA forward. As Che-Espinoza, one of my pillars of spiritual foundation, writes: Heart work demands attention to one’s own complexity and the narrative that we live with, day in and day out…The mind is a valuable tool for our becoming activist theologians, but the heart and the ability to (em)body our feelings generate the most robust action and help tie together thinking with action. The heart of becoming is in finding the plumb line of one’s own story. That’s the heart of activist theology.

0 Comments

Shelley Butler, Beloved Community Communications Team No Question That Reparations Are Owed After coming into the Parish Hall for Wellspring Wednesday on January 31, 2024, and saying hey to a few people, I took a spot at the front in one of the only seats left for the panel discussion, “The Process of Politics and Reparations in Saint Paul,” sponsored by the Unity Racial and Restorative Justice Team. Unity member Russel Balenger spoke about being a descendent of enslaved people, and about growing up in Rondo before being displaced. In a brief film, we heard Bridgett Floyd, sister of George Floyd, speak about the enslaved ancestors who managed to acquire several hundred acres of farmland in the South after emancipation only to have it stolen from them. Our country and our state of Minnesota were built on stolen land and free labor. Reparations are not an abstract idea relating to people over 100 years ago. The action is personal to Russel and Bridgett and every descendent of an enslaved family member. And it is about the continuing legacy of slavery: trauma, lost generational wealth, health care issues, housing discrimination, disproportional imprisonment, the destruction of the Rondo neighborhood, and more. We learned that Minnesota has the third-largest racial wealth gap in the country. It should be personal to all of us. Jane Prince has worked on reparations for years and is now fresh off the City Council and a Unity Church member. She said, “Reparations [are] a federal debt.” The work in St. Paul is a start, as are the 116 other proposals to do with reparations that have passed around the country. Reparative Work by the St. Paul City Council To bring us up to date, Trahern Crews, a Black Lives Matter Minnesota leader and one of the conveners of St Paul’s Reparations Advisory Committee, walked us through the years of study and work completed by himself, Balenger, Prince, and many others that led to successful reparations work in St. Paul. Highlights include:

Independent of the City Council, Mayor Melvin Carter established the Rondo Inheritance Fund to help displaced Rondo families purchase housing. And while information on the Inheritance Fund is on the city website under “City Council Reparations Efforts,” it is not related to the commission. Due to a large number of applicants, the city is no longer taking applications for this fund. What You Can Do Right Now The history so far is important, but to hear direct-experience testimony is to witness the pain and hopefully, to become allies in the work of reparations. Thus, the call to immediate action. Here’s what you can do:

Questions for Further Thought

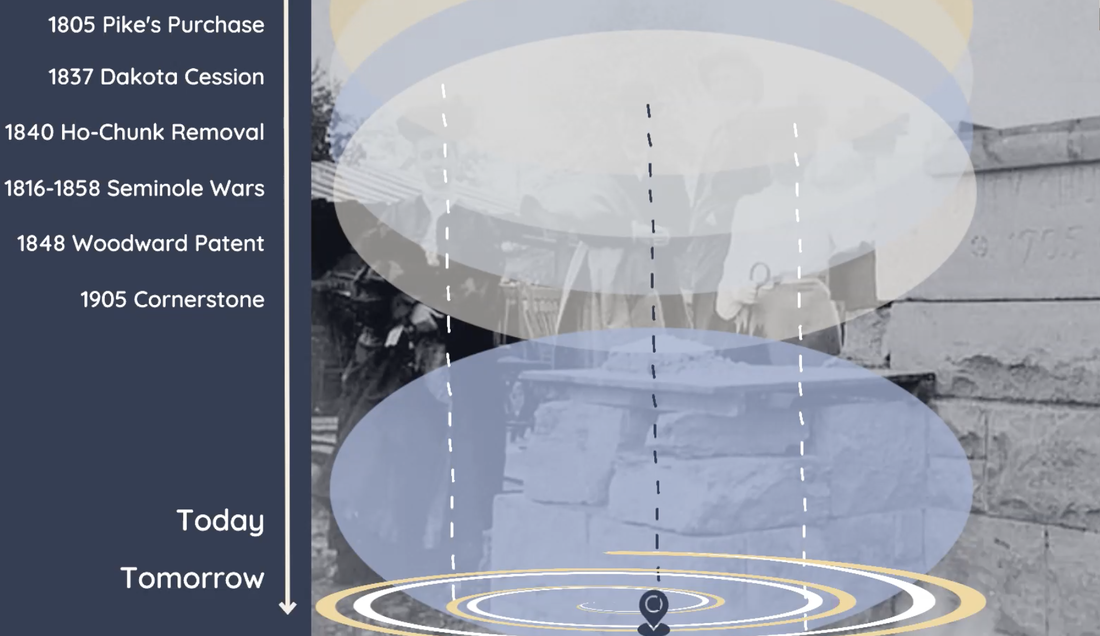

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications and Indigenous Justice Ministry Teams Unity Church-Unitarian sits on land stolen from the Dakota people. We read this in our weekly Order of Service and proclaim it prior to the start of most church meetings, our own pledge of allegiance of sorts. However, what does this really mean and how did it happen? Unity’s Act for the Earth and Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Ministry Teams series, “Truth Telling and Healing: Indigenous and Environmental Justice," included a close look at how Unity came to be located on Dakota land (Land and Reparations). During this presentation in March 2023, Jessica Intermill of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light and Intermill Land History Consulting, invited us to look at history differently. Unity Church-Unitarian sits on land stolen from the Dakota people. We read this in our weekly Order of Service and proclaim it prior to the start of most church meetings, our own pledge of allegiance of sorts. However, what does this really mean and how did it happen? Unity’s Act for the Earth and Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Ministry Teams series, “Truth Telling and Healing: Indigenous and Environmental Justice," included a close look at how Unity came to be located on Dakota land (Land and Reparations). During this presentation in March 2023, Jessica Intermill of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light and Intermill Land History Consulting, invited us to look at history differently. History is typically laid out chronologically in books: American Revolution, Slavery, Western Expansion, and the Civil War. However, slavery occurred before and during the Revolution and played a part in westward expansion. “Today’s physical landscape has everything that came before us right now,” explained Intermill. The question is, “What does it mean to take responsibility for a past that’s not past?” Intermill mapped the location of Unity Church and then peeled back the layers of events on our land since the occupation of stolen Dakota land. She started with the arrival of United States General Zebulon Pike at the convergence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers who declared it an ideal spot to build a fort (Fort Snelling). In 1805, the United States Congress purchased from the Dakota people 155,000 acres of land at this spot for practically nothing. Through deception and manufactured devaluation, land that should have brought $300,000 to the Dakota people possibly brought them the remains of $2,000 worth of goods. Keep in mind that Bdote, the convergence of these two rivers, is where human life began according to the Dakota. So, this is sacred land which started out as a place of genesis and eventually became the site of genocide. Things didn’t fare any better when the U.S. government purchased more land surrounding Fort Snelling through the 1837 Sioux Treaty. Here again, treacherous cruelty prevailed — this time the Dakota only received $16,000 through this treaty while those who had intermarried with them received $110,000, and $90,000 covered fabricated Dakota debt created by white people (many of whom were of the federal government). This thievery stemmed from the demise of the fur trade and a need for those traders to come up with a new source of income. From there, the U.S. government paid soldier Sam Taylor for his work with a New York regiment with a voucher for a section of land between St. Clair and Marshall Avenues. Taylor didn’t want the land and sold it to land speculators, and it eventually wound up in the possession of a man named Woodword. So, back to Intermill’s original question: “What does it mean to take responsibility for the past that’s not past?” Participants in the final session in the Truth Telling and Healing series held last month shared their stories of how the programs had impacted them. These are some of the themes that emerged:

The group then considered next steps for themselves as individuals and for Unity as a congregation:

Among the suggested resources to continue the Indigenous and environmental justice journey is the Native Governance Center's Beyond Land Acknowledgment Guide. This is one avenue Unity’s Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Team will explore as it plans future learning and spiritual growth opportunities. Be sure to also check out Act for the Earth activities. Meanwhile, continue your own spiritual and educational journey by exploring: |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

July 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |