Ray Wiedmeyer, Beloved Community Communications Team I’ve been thinking a lot about land ownership the past couple years. Just a bit into the pandemic, I attended the Sacred Sites Tour in the Twin Cities led by Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs, a member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation. Jim Bear spoke clearly about the broken promises, the broken treaties that would remove the vast majority of Indigenous Peoples from the land that is now the Twin Cities, and efforts in the 19th century to banish them completely from Minnesota. All that after having been told, in fact promised, that the white colonizers would share the land. Indigenous Peoples understood that land could not be owned, that no one could claim ownership. If anything, they were of the mindset that the land owned them; that humans were no more important than the land on which they lived and that gave them sustenance. After Rev. Jim Bear’s presentation, I realized that I was now part of the story. I own land in St Paul. And I own land in Wisconsin a mile or two from the scattered bits of the St Croix Chippewa reservation where 3.8 square miles is all the tribe has left of original homelands that once covered thousands of square miles. I am not someone disconnected from the past; I am part of the historical timeline. To be perfectly honest, it totally changed how I see the land we own. Given the choice to see the land as a commodity or to see myself as the caretaker of that land was a choice I could make. I choose now to think of myself as caretaker. But I am caretaker of land that was taken from folks who lived here long before my white ancestors arrived. With that in mind, how do I live with the principles of Unitarian Universalism, the Unity Ends Statements that I was so excited about in 2018, and the ritualized land acknowledgment we espouse every Sunday? What was my next right action? What kind of discomfort, what kind of pain did I need to be willing to work through to see the change I wanted to see in the world? I have been living with that discomfort for some time now. It was scary but I asked my partner if we could give the Wisconsin land we own back to the local St Croix Chippewa Tribe. It was scary because I feared she would say, “No.” You see, it is our happy place. The place we go to disconnect, and we love it dearly. She said, “Of course we should give it back.” The next hurdle for me was fearing what our neighbors might think. Was there really a fear in me that the tribe would not be good neighbors? Surprisingly, I needed to move past those racist attitudes that bubbled up in me. I needed to give up on the idea that only I could be the perfect caretaker of that land. Time passed. The inertia of white privilege can and will make one forget one’s best intentions. But eventually we contacted Jessica Intermill of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light. Jessica centers much of her legal work representing Native tribes and I am acquainted with her workshops on reparations. She let us talk through our questions and concerns about giving the land back. She introduced us to the concept of “rematriation,” or restoring the matriarchal relationship between Indigenous Peoples and ancestral land. Upon her recommendation, we contacted the St. Croix Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Chippewa Tribe of Wisconsin, who then consulted their lawyer, who then approached their tribal council, who considered our request, and told us they would love to have the land back. We then needed to find a Wisconsin real estate lawyer, preferably native, who would do the necessary legal work. Months passed. It is so easy to just move along in one’s privilege and not to keep on task. Needing to finish this story, literally, for this August newsletter was the additional push I needed. We met with Richard Lau, one of my recent associates on the Ministerial Search Team at Unity Church who practices real estate law in Wisconsin. We talked through various ways of giving the land back, and he has begun the work to transfer the land. Recently I heard the phrase, “It is one thing to begin to be woke but eventually one needs to get out of bed.” We moved from a place of awareness to the place of discomfort, and finally found the price we are willing to pay to be in right relationship with the world we wish to see. It has been a long journey but worth every step taken.

0 Comments

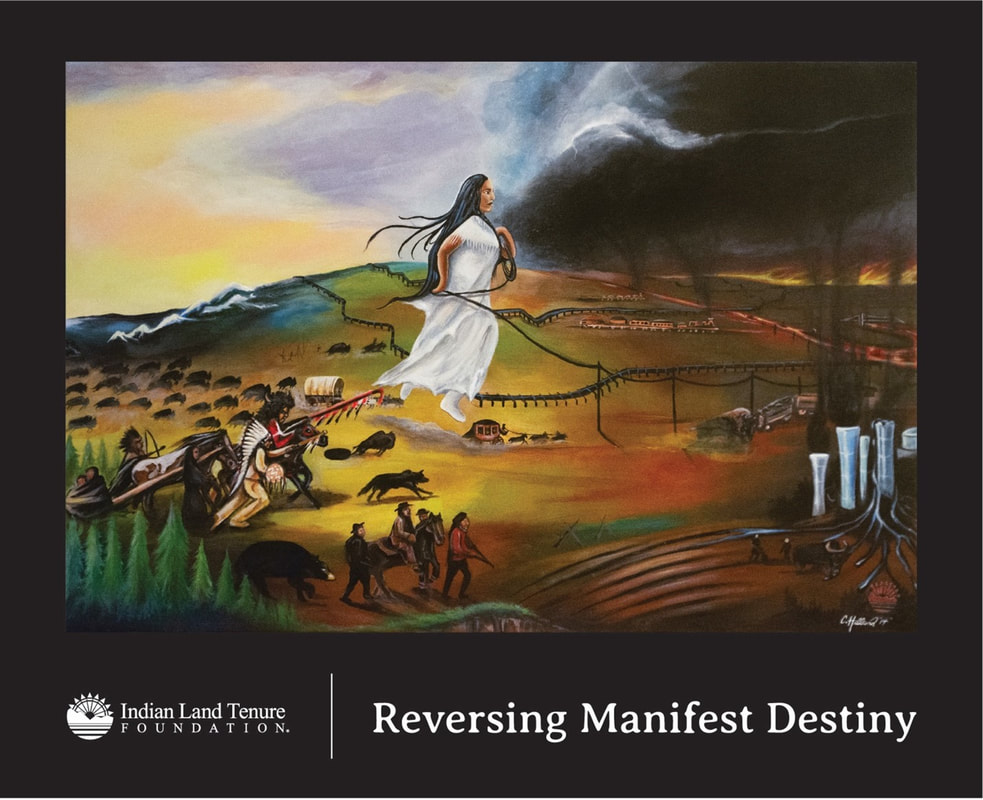

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team I believe stories change hearts and minds, and we are in such civic and social conflict that we need stories that help create conditions of possibility for social healing…. When we lead with our heart, we learn that our mind and body more closely align with putting thought into action. In short, faith without works is dead. Faith, being that thing that animates our heart, our internal narrative of how we make sense in this vast world, is compelled by the questions of what and how: What do we do? How do we do it? These two questions—what do we do and how do we do it?—are central to the conversation surrounding reparations to Indigenous communities and nations for treaties broken and land stolen. Several years ago when members of Unity Church-Unitarian began a conversation with Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Mohican) of Healing Minnesota Stories about efforts to restore and maintain Indigenous language, culture, and land, the idea of “land back” remained elusive, something we would figure out years from now. However, today reparations can take on many forms well beyond the singular view of returning the land on which Unity sits to a Dakota community and leasing it from them. Before any final solution to American history can occur, reconciliation must be effected between the spiritual owner of the land—American Indians—and the political owner of the land—American Whites.” The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery and its Repair Network are spearheading efforts to pass a surtax on Minnesota real estate sales to support Indian programs run by Indian people. The proposal is called the Indian Recovery Act or IRA. Here is an overview of the plan to be introduced during Minnesota’s 2025 legislative session:

This proposal is the culmination of work by Dakota and Ojibwe tribal councils and their allies. Originally intended to be introduced during the 2024 Minnesota legislative session, the parties involved determined the original bill needed some tweaking, and would fare better during a non-election year. The delay gives us extra time to help build support for the IRA. For additional information, contact the Repair Network’s Legislative Team at [email protected] or call 612-440-4526. They are looking for volunteers to speak at churches and other faith communities, write letters of support, testify before legislative committees (when the time comes), and other tasks that will move the IRA forward. As Che-Espinoza, one of my pillars of spiritual foundation, writes: Heart work demands attention to one’s own complexity and the narrative that we live with, day in and day out…The mind is a valuable tool for our becoming activist theologians, but the heart and the ability to (em)body our feelings generate the most robust action and help tie together thinking with action. The heart of becoming is in finding the plumb line of one’s own story. That’s the heart of activist theology. Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team and Indigenous Justice Ministry Team  Makoce Ikikcupi - Mountain Lake Makoce Ikikcupi - Mountain Lake We stand on the homelands of the Dakota Nation. We honor with gratitude the people who have stewarded the land throughout the generations and their ongoing contributions to this region. We acknowledge the ongoing injustices that we have committed against the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations, and we wish to interrupt this legacy, beginning with acts of healing and honest storytelling about this place. This is Unity’s land acknowledgment. Ministers used to proclaim it each Sunday. Now it's printed in the order of service. No less important in written form, this land acknowledgment calls us to move beyond words to action. But what does this mean? Often conversation about repair and reparations to Indigenous peoples centers around land back proposals. One example is the University of Minnesota’s efforts to address its violent history with Minnesota’s Indigenous people. At the recommendation of the Towards Recognition and University-Tribal Healing Project, the University of Minnesota is in the process of returning 3,400 acres of land to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. This is but a small portion of the 94,631 acres the federal government gave to the University of Minnesota as part of the Morrill Act in 1862 to set up “land grant” colleges for which they paid the tribes $2309. However, congregations and individuals can participate in land back efforts in other ways. The Mni Sota Makoce Honor Tax is a fund to which people and groups can voluntarily contribute to the Lower Sioux Community. According to the mnhonortax.org website, “The tax is a voluntary payment made directly to the tribe by those who live in, work on, and visit traditionally Dakota land within Minnesota.” One can think of this tax as “rent,” “repair,” or something else. In Minnesota, a bill will be re-introduced that would establish tax tied to real estate sales and the creation of a Council on Native Programs and a Native Recovery Fund. A tiny surcharge on real estate sale transactions would be part of closing costs and have almost no impact on the buyer but has the potential to raise millions for Native American-driven programs. Doe Hoyer is an organizer and songleader with the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery, and coordinates the Repair Network. At the January 24, 2024, Wellspring Wednesday, they will be talking more about this bill and the upcoming session of the Minnesota Legislature. The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery has its roots in the Mennonite Church and calls on Christian congregations to address the “extinction, enslavement, and extraction done in the name of Christ on Indigenous lands.” However, that doesn’t mean UUs cannot take part. Our ancestry is based in Christianity and while we don’t necessarily identify as Christian today, we do have a responsibility to disrupt the culture our ancestors helped create. Consider that our Unitarian ancestors have complex histories, landing on both sides of oppression. Unitarians held leadership positions in the creation and building of the United States. And several played prominent roles in promoting American exceptionalism, specifically white Anglo-Saxon supremacy that laid the foundation for the “Stand Your Ground” culture of today. Even our UU ancestor Theodore Parker — leading abolitionist and one of the "secret six" financial supporters of John Brown and the raid on Harpers Ferry — could not entirely escape the racial prejudice of his time and place and the racialized interpretation of history. So we UUs have our own confessing, lament, and truth-telling to do. We also have a variety of opportunities to respond to calls for solidarity with Indigenous neighbors. Unity's Indigenous Justice (IJ) Team collaborates with the Coalition for Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery and its Repair Network, which provides opportunities to work alongside Indigenous groups to strengthen their culture and reclaim land. Makoce Ikikcupi (Land Recovery) is one example. This is a project of reparative justice on Dakota land in Minisota Makoce (Minnesota) that seeks to bring some Dakota people home, re-establish their spiritual and physical relationship with their homeland, and ensure the ongoing existence of Dakota People. Two villages of earth lodges are currently under construction in Mountain Lake and Granite Falls where Dakota people can live following traditional practices. More villages are planned as additional land is reacquired. IJ member Helen Pohlig has helped with the Mountain Lake site. If we truly wish to interrupt the doctrine of domination legacy, consider one or more of these ways to begin acts of healing and honest storytelling about this place. |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

July 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |