|

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team and Indigenous Justice Ministry Team  Makoce Ikikcupi - Mountain Lake Makoce Ikikcupi - Mountain Lake We stand on the homelands of the Dakota Nation. We honor with gratitude the people who have stewarded the land throughout the generations and their ongoing contributions to this region. We acknowledge the ongoing injustices that we have committed against the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations, and we wish to interrupt this legacy, beginning with acts of healing and honest storytelling about this place. This is Unity’s land acknowledgment. Ministers used to proclaim it each Sunday. Now it's printed in the order of service. No less important in written form, this land acknowledgment calls us to move beyond words to action. But what does this mean? Often conversation about repair and reparations to Indigenous peoples centers around land back proposals. One example is the University of Minnesota’s efforts to address its violent history with Minnesota’s Indigenous people. At the recommendation of the Towards Recognition and University-Tribal Healing Project, the University of Minnesota is in the process of returning 3,400 acres of land to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. This is but a small portion of the 94,631 acres the federal government gave to the University of Minnesota as part of the Morrill Act in 1862 to set up “land grant” colleges for which they paid the tribes $2309. However, congregations and individuals can participate in land back efforts in other ways. The Mni Sota Makoce Honor Tax is a fund to which people and groups can voluntarily contribute to the Lower Sioux Community. According to the mnhonortax.org website, “The tax is a voluntary payment made directly to the tribe by those who live in, work on, and visit traditionally Dakota land within Minnesota.” One can think of this tax as “rent,” “repair,” or something else. In Minnesota, a bill will be re-introduced that would establish tax tied to real estate sales and the creation of a Council on Native Programs and a Native Recovery Fund. A tiny surcharge on real estate sale transactions would be part of closing costs and have almost no impact on the buyer but has the potential to raise millions for Native American-driven programs. Doe Hoyer is an organizer and songleader with the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery, and coordinates the Repair Network. At the January 24, 2024, Wellspring Wednesday, they will be talking more about this bill and the upcoming session of the Minnesota Legislature. The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery has its roots in the Mennonite Church and calls on Christian congregations to address the “extinction, enslavement, and extraction done in the name of Christ on Indigenous lands.” However, that doesn’t mean UUs cannot take part. Our ancestry is based in Christianity and while we don’t necessarily identify as Christian today, we do have a responsibility to disrupt the culture our ancestors helped create. Consider that our Unitarian ancestors have complex histories, landing on both sides of oppression. Unitarians held leadership positions in the creation and building of the United States. And several played prominent roles in promoting American exceptionalism, specifically white Anglo-Saxon supremacy that laid the foundation for the “Stand Your Ground” culture of today. Even our UU ancestor Theodore Parker — leading abolitionist and one of the "secret six" financial supporters of John Brown and the raid on Harpers Ferry — could not entirely escape the racial prejudice of his time and place and the racialized interpretation of history. So we UUs have our own confessing, lament, and truth-telling to do. We also have a variety of opportunities to respond to calls for solidarity with Indigenous neighbors. Unity's Indigenous Justice (IJ) Team collaborates with the Coalition for Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery and its Repair Network, which provides opportunities to work alongside Indigenous groups to strengthen their culture and reclaim land. Makoce Ikikcupi (Land Recovery) is one example. This is a project of reparative justice on Dakota land in Minisota Makoce (Minnesota) that seeks to bring some Dakota people home, re-establish their spiritual and physical relationship with their homeland, and ensure the ongoing existence of Dakota People. Two villages of earth lodges are currently under construction in Mountain Lake and Granite Falls where Dakota people can live following traditional practices. More villages are planned as additional land is reacquired. IJ member Helen Pohlig has helped with the Mountain Lake site. If we truly wish to interrupt the doctrine of domination legacy, consider one or more of these ways to begin acts of healing and honest storytelling about this place.

0 Comments

By Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy and Rev. KP Hong, Beloved Community Communications Team In his book, Faith Without Certainty: Liberal Theology in the 21st Century, UU theologian Paul Rasor lays out plainly how liberal religion is fraught with challenges to examining spirituality and putting it to work to address racism. He writes:

Unity recently concluded a three-part workshop, “Spiritual Practice: Discovery and Transformation,” that brought participants together in conversation and exploration of how to do what Rasor describes: develop spiritual practices that engage in antiracism work. To be effective, one cannot exist without the other, says Rev. KP Hong, Minister of Faith Formation and one of the workshop leaders. Anything less continues to support white supremacy. This was precisely the question Martin Luther King, Jr., brought into prophetic focus, wondering how spiritual practice on Sunday morning could be emblematic of “one of the most segregated hours” in America, a racialized spiritual practice in collusion with white supremacy. And equally significant, King relentlessly interrogated what racial justice requires and, with other members of the civil-rights generation, formulated nonviolence as the “only weapon that could cut and heal at the same time,” an antiracist practice necessarily grounded in disciplined spiritual practice. Unity provides many opportunities to engage in antiracist multicultural action. This workshop sought to look at the faith formation side of things, and raised many questions as participants considered how to create or enhance their own practices. One example: “How do I know I’m not living out my value of perfection?” Workshop leaders offered this advice: Is your practice me-centered or other-centered? Does it make you just feel good or do you push yourself to go beyond your comfort zone, to push boundaries? To disrupt? Perfectionism is me-centered. When one pursues excellence, it can be we-centered if benefiting others is your goal. Spiritual practice can take many forms. Body awareness work, zazen meditation, prayer, writing, art, walking or working in the natural world, chalice circles, worship, Lectio Divina, and music are among many possibilities. The key here is the word “practice.” Whatever you choose, commit to doing it each day, with intention and discipline. The first session established an understanding of spiritual practice as our way of being with the (w)holy, with what is greater than me and the countless boundaries that we erect to establish, fortify, and protect our preferred sense of self. At its core, then, spiritual practice summons us to the borders of our being, knowing, and ways of moving through the world – whether the borders of my personal identity or my tribe or the checkpoints along the Rio Grande. What happens at the border with the Other and the Not-Me? As King reflected on the Parable of the Good Samaritan, “the first question that the Levite asked was, ‘If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?’ But then the Good Samaritan came by, and he reversed the question: ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?’” The second session explored what those practices might look like, stepping beyond the border of theory into practice, beyond the border of understanding into experiencing. The third and final gathering brought together spiritual practice and antiracist practice as an inescapable mutuality, a “double helix” in which the parallel helices of spiritual practice and antiracist practice co-create, authenticate, and prophetically keep each other from being co-opted and appropriated by white supremacy encoded throughout our history, culture, and structures. Participants will be invited to a follow-up session in February to review their progress. However, you may attend in February even if you did not take part in the fall series. To find out even more about spiritual practice, check out the Spiritual Practice page on the Unity Website to get some ideas. Of particular interest are the Spiritual Practice Packets organized around our monthly themes. You do not need to be in a chalice circle to use the packet. Find copies in the kiosk in the main lobby and on the Spiritual Practice bulletin board just outside the kitchen. The packet this month centers on the worship theme for October, “confessing.”

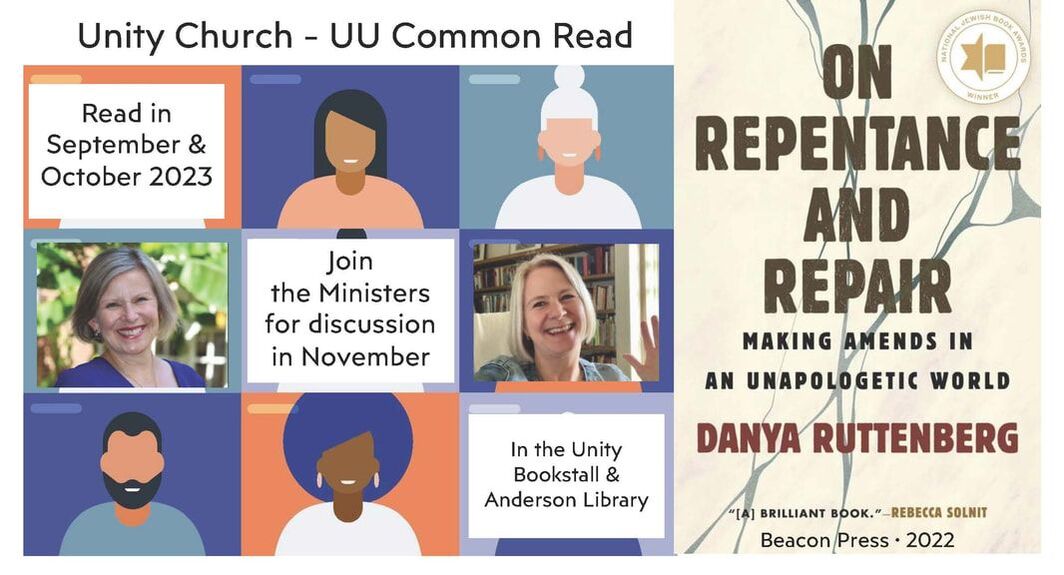

By Shelley Butler, Beloved Community Communications Team and Library-Bookstall Team A UU Common Read can take us on a powerful journey into what it means to be human and accountable in a world filled with both pain and joy. —Unitarian Universalist Association

A Unity friend told me recently that her husband was exhilarated by our congregation read book, On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World by Danya Ruttenberg; that his copy was full of bookmarks and notes in the margin, and that he was planning to purchase the book for others in their family. This is not something you’d necessarily expect to hear about a book that teaches us in five steps to do the work of repentance personally and collectively, but we hope that his enthusiasm will inspire you and others to participate in the read and this work. Dismantling white supremacy and making reparations for the shame of slavery or reparations for stolen land and genocide of Native Americans often feels overwhelming. Even figuring out how to right a wrong against just one person we have harmed can provoke anxiety. But, as is quoted in On Repentance and Repair, “If you believe that you can do damage, believe that you can fix it. If you believe that you can do harm, believe that you can heal.” Let’s not let the enormity of what we need to do cut us off at the knees. This book, the opportunity to delve more deeply into it in an Antiracism Literacy Partners group, and the “Repentance and Repair in Our Lives and Relationships” discussions coming up at Unity in November provide us with the guidance to continue the antiracism and right relations work we’ve already started at Unity, but also support those of us who may be just beginning this work, step by step. In the book, Rabbi Ruttenberg outlines the path based on the work of 12th century-medieval Sephardic Jewish philosopher Moses ben Maimon, more commonly known as Maimonides, and deftly applies these principles to today. The first step is “naming and owning harm,” or confessing (our worship theme for October). Ruttenberg acknowledges the challenge, but also the tendency to minimize harm by making excuses and justifications. How often have we heard and even said, “But I didn’t mean to”? She writes, “Addressing harm is possible only when we bravely face the gap between the story we tell ourself — the one in which we’re the hero, fighting the good fight, doing our best, behaving responsibly and appropriately in every context — and the reality of our actions.” It may be true that our intentions are good and that we are doing our best, but that doesn’t negate harm we’ve caused or inherited nor the responsibility to make amends. The steps beyond confession — both public and private — include change, restitution, consequences, apologies, and making better choices; or in other words, transformation that leads to healing and a more just world. So many important questions are answered here: How do we handle harm when we see it around us? In an antiracism workshop at Unity, there was talk of weaponizing the traits of white supremacy culture listed by Tema Okum. What is the difference between calling out harm when we see it and weaponizing a tool that helps us understand it? What about the harm caused by the institutions, like Unity Church, or workplaces, schools, universities, or social groups; justice systems—policing, courts, prisons; and the nation? How do we hold ourselves and these larger arenas accountable, and what is our responsibility? Is national repentance, for example, possible; and can we learn from Germany and South Africa? Beyond accountability, how can we atone and make amends? Even as I write this, the questions loom large, and on my own, I could never answer them. But in a community such as ours that values truth, honest storytelling, and healing, and with resources, workshops, and discussions like the Unity-UU Common Read, maybe together we can summon the bravery to begin and the willingness to continue the work, and the faith that “on the other side of transformation is another more whole, more full, more free way of being, one that we can’t fully imagine from here.” Sounds a lot like a walk towards beloved community, doesn’t it? Won’t you join us? On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World by Danya Ruttenberg. Beacon Press, 2022. In the Unity Bookstall (paperback, $18), and in the Anderson Library (202.2 R). Unity–UU Common Read Events: Repentance and Repair in Our Lives and Relationships Led by Rev. Kathleen Rolenz and Rev. Lara Cowtan

Antiracism Literacy Partners, Tuesday, December 5, 2023. Meet to learn about the program and sign up for a group to take a deeper dive into On Repentance and Repair. On Zoom, register today! |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

July 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |