|

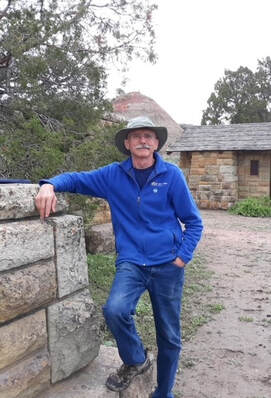

Ray Wiedmeyer, Beloved Community Communications Team, Ministerial Search Team, Mano a Mano Warehouse Manager  I like to think I am free from bias and that’s a rather comfortable feeling. This spring however I had an uncomfortable thought that gave me pause. I had been listening to a lecture given by a male minister and I noticed how comfortable I was with the delivery and message. The comfort felt quite close to how I felt upon hearing many of Rev. Rob Eller-Isaacs’s sermons. There were a couple moments of comfort with that awareness, but then discomfort followed close behind. Was the comfort I was feeling a sign of some bias I had around white male ministers? I didn’t want to believe that, but the thought has stuck with me for months. You see, I had just been nominated to be a possible candidate on the Ministerial Search Team (MST). I was excited about the possibility of serving but I was now conscious of the fact that any kind of unchecked bias would not serve me, the team, or the congregation. If I was to be a valuable member of the MST, I needed to not let my biases rule my thinking. I realized I might have some work to do. Recently I attended a workshop at Unity led by consultant Alfonso Wenker called “Engaging Awareness, Disrupting Dominance.” The first lesson that day was to notice when a like or irritation came up for me around another person and to notice how that showed up in my body. The ministerial lecture months before had left a sort of soft glow that I had not experienced in a while. More recently, working with a volunteer at Mano a Mano, I found myself assuming certain things because of the woman’s shy demeanor and ethnic background. I came to a certain judgement that first meeting only to find at later volunteer sessions that in her other paid employment as a student, she used skills I would never have imagined she had. My bias based simply on her gender, her demeanor and her ethnic heritage made me fall for the “single story” that many of us may have heard about from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on YouTube. Let me be clear I know we all have biases, that’s quite normal. It’s when that bias becomes a perceived identity, we lay on another, that we get into trouble. We then make judgements about their character, skills, and life experience. It's a “single story” that helps me keep the dominant culture dominant. It allows me to only see their age, skin color, gender or hair style as the important measure of their worth. It’s a snap judgement that might help me find my people, but knowingly or not, excludes others, and keeps me from really being ready for the Beloved Community that I say I yearn for. It brings me back now to actually serving on the ministerial search team. In cottage meetings and through the congregational survey, the Unity congregation shared with us what you think is important in a new settled minister. You have shared with us the strengths and the capacity you think that person needs to have, to help us grow into the community we seek to be. If we stop at identity, we may very well fail to see the "other’s" capacity. Identity and capacity are two different but very important parts of who someone is. One’s skin color, gender, hair style, age or perceived physical ability should not be ignored but also should not block us from seeing another’s capacity to do the job. How do we discover that capacity? How is that capacity shaped and expressed by their identity? This is the work of the MST. And hopefully yours as you move out into the world. That brings me to the last step Alfonso talked about once we make that connection between identity and capacity. Heaven knows how many books I have read seeking to raise my awareness, but how do I put that studied awareness into change? I must practice looking beyond my bias. It does not come naturally. So, if you see me pause, take a deep breath, share that I might have a certain bias or make certain assumptions about something before giving an opinion, you will know I am working on my white male privilege. I am noticing a bias, naming it, and then hopefully navigating in a way that does not center "me" but rather centers the "we" that creates Beloved Community.

0 Comments

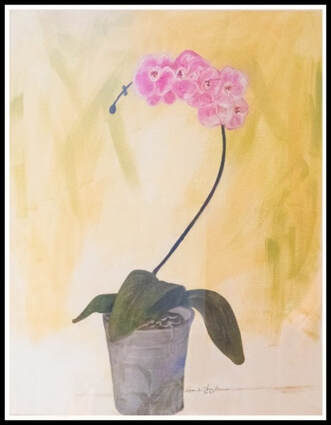

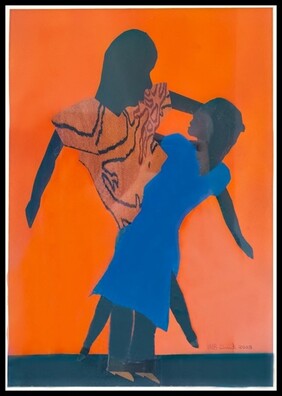

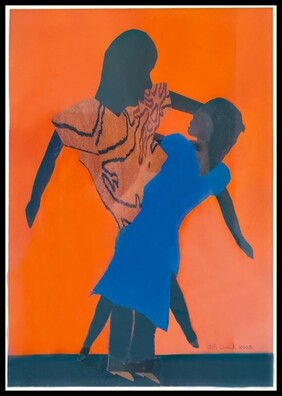

Paul Rogne, Guest Writer from Unity's Art Team  In November 2023, the Unity Church Art Team featured a Parish Hall exhibit of artwork by Rose and Melvin Smith, esteemed elders in the African American artist community of the Twin Cities. It was the culmination of a journey that began in 2021 when the art team sought these artists out hoping to purchase one of their paintings. After visiting with the art team and touring Unity to see the permanent art collection, Rose and Melvin agreed to sell one of Rose’s fine paintings, an image of a woman she met in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. That painting now hangs in the Center Room. The Smiths told us they were impressed with Unity and wanted to thank our church community for its commitment to promoting the arts. Their interest and ours resulted in an exhibition of their most recent work, none of which had ever been shown. Over the years, the artist couple has exhibited several times in New York City; their works depicting scenes and impressions of life in the history of the Rondo neighborhood are currently being featured in a Manhattan gallery. They have also exhibited in Chicago, Oklahoma, and at the Weisman Museum in Minneapolis. It has been a privilege to have them exhibit new work at Unity Church. Rose’s latest is a series of canvases capturing flowers arranged in the style of the Japanese art form, Ikebana. Melvin’s colorful collages were inspired by the classical American dance form the Jitterbug. Why did the art team reach out to these particular artists? In addition to the quality of the work, the team looks to questions prompted by Unity’s Ends Statements (2018) in considering the criteria to use in selecting artists for this program:

If our ends statements plus Unity’s mission to “transformation through a free and inclusive religious community …” are to be taken seriously, then the art team is determined to move forward on them. What shows that movement up to this point? Not only have we shown and continue to invite artists of greater diversity regarding ethnicity, race, gender, culture, religion, sexual identity, socioeconomic, physical ability, and neurodiversity to participate in Unity’s monthly exhibitions but we have also expanded the church’s permanent art collection featured throughout the building to include this diversity. There are now many more artists from our greater community represented on our walls including artists of color, LGBTQ+, Hmong, Karen, and more. In 2022, Mica Lee Anders, a Rondo neighbor and accomplished artist and educator, led a group of Unity volunteers to create an eye-catching new Foote Room mural. The shape of the overall design is familiar to Unitarian Universalists — a chalice. In October 2023, the Parish Hall featured works created by artists incarcerated in Minnesota correctional facilities. These talented artists claim roots in a variety of ethnicities and cultures. Art From the Inside, the organization that brought them here, was able to hold a successful fundraiser at Unity, and was the recipient of a Sunday offering —another example of how the art team strives to act on our ends. We know there is much more to do, but it is exciting and rewarding work. The art team urges everyone at Unity Church to be curious. Take a moment to look at the artwork as you wander through the hallways or gather for a meeting. Chances are you are seeing art that represents the concerns, ideas, thoughts, and/or feelings of a member of our greater Beloved Community. That should be reason enough to take notice. A Rare Treat: Rondo Residents Rose and Melvin Smith are Unity’s Featured Artists in November11/10/2023 By Paul Rogne, Unity Church Art Team On Friday, November 10, from 5:00-7:30 p.m., an open reception will be held at Unity Church where visitors can view the art and meet the artists. Light refreshments will be served. The Unity Church Art Team is pleased to open an exhibition of paintings by nationally known Rondo artists, Rose and Melvin Smith in Unity’s Parish Hall. The show is the culmination of a journey that began in 2021 when Unity's Art Team sought out the esteemed artists and longtime Rondo neighborhood residents, hoping to purchase one of their art works. After a tour of Unity’s permanent art collection, they agreed to sell one of Rose’s paintings, an image of a woman whom she met in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. That painting now hangs in the Center Room. The Art Team and Unity Church were doubly privileged when the Smith’s consented to a full exhibition of their latest paintings, which have never before been shown. The Smith’s paintings have been featured at galleries in New York City, Chicago, Oklahoma, and at Minneapolis’s Weisman Museum. The new works include a series of paintings by Rose depicting flowers arranged in the style of Ikibana, the art of Japanese flower arrangement. Melvin’s works are colorful collages inspired by the classical American dance form, the Jitterbug.

The exhibition will be on view in Unity’s Parish Hall through November 2023. |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

April 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |