|

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team Reparations. This word elicits many responses, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual: fear, anticipation, lament, joy, confusion, clarity of purpose, resistance, courage. Reparations means different things to many people. Reparations to the descendants of slavery might be monetary. Reparations to Native American nations would more likely be through returning land, enforcing tribal rights, and honoring treaties. This month, Unity Church delves deeper into conversation about reparations within and among congregants in various spaces, defining what it is and is not, exploring the difference between individual and organizational reparations. I am participating in the Reparations Learning Table, a four-part series about the basics of reparations, offered by Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light. Led by Jessica Intermill and Liz Loeb, we began with this working definition of reparations:

With this definition in mind, Intermill and Loeb explained what reparations is not:

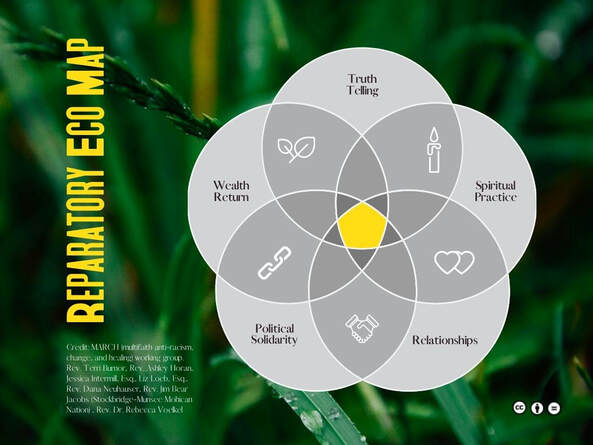

Perhaps the easiest way to visualize the concept of reparations is to refer to a graphic that Intermill calls the Reparatory Eco Map. Reparations is the intersection of the five sectors — Truth Telling, Spiritual Practice, Political Solidarity, Relationships, and Wealth Return. All are essential, and yet none is sufficient on its own. Each component leads to another with no starting point and no stopping point, meaning that regardless of what portal you enter, the act of reparations is lifelong, generational work. This is about shifting how we live in connection with others and with history. Learning the language of reparations is essential to making this work accessible, allowing anyone to take those first steps. We may enter the Eco Map at different portals. I began at Truth Telling. My white parents could not conceive any more children after me so they turned to adoption. My father had a strong interest in the Ojibwe community and so in 1966 my parents adopted a baby from the White Earth Reservation. In spite of their efforts to connect my brother to his heritage, white society on the North Shore of Lake Superior wasn’t having it, and my brother experienced racism such that he ultimately became estranged from us. In addition, thanks to diligent family history work by one of my sons, I now know that one of my ancestors dealt in land theft from an Indigenous nation in Massachusetts. We may have identifiable personal reasons to get involved with reparations, or we may simply know that we are responsible for the continuation of today’s disparities. Whatever the reason, our work must disrupt systems, not merely apply band-aids and call it good. For those who want to learn more about reparations, be sure to register for the Truth and Healing Indigenous and Climate Justice Series sponsored by Unity’s Indigenous Justice and Act of the Earth Community Outreach Ministry Teams. Session Five will be held Wednesday, March 1, at 7:10 p.m., in Robbins Parlor. The topic is land and reparations and the guest speaker will be Jessica Intermill from Minnesota Interfaith Power & Light. You may also register for the remaining Reparations Learning Table sessions. Previous meetings were recorded and are available to view upon registration. Resources Reparatory Eco Map credit: MARCH (multifaith anti-racism, change, and healing) Rev. Terri Burnor; Rev. Ashley Horan; Jessica Intermill, Esq.; Liz Loeb, Esq.; Rev. Dana Neuhauser; Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation, Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voekel

0 Comments

Pauline Eichten, with input from the Beloved Community Staff Team It’s timely to have this article in December, when our worship theme is wonder. How might we wonder together, with curiosity instead of judgment, about the challenge of reparations? Are we making any progress toward racial justice, as an interviewer wondered in March of 1964, when he asked Malcolm X if progress was being made. “No, no,” Malcolm replied. “I will never say that progress is being made. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. The progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even begun to pull the knife out, much less heal the wound.” And when the interviewer attempted to ask another question, Malcolm interjected, “They won’t even admit the knife is there.” “Pulling the knife out” is an essential step, but it is only an act of suspending the harm. It does not “heal the wound” because it is not an act of remediation or reparation. Repairing the wound requires those culpable to make amends and restitution for the harm inflicted. The claim for restitution anchors historically on our government’s failure to deliver on the promised 40-acre land grants to the newly emancipated, a failure that lay the foundation for the enormous wealth gap that exists today between Black and white people. The case for reparations does not center exclusively on “slavery reparation” but seeks accountability for the atrocities of legal segregation we know as the Jim Crow era and the ongoing atrocities, including mass incarceration, credit/housing/employment discrimination, a criminal justice system and policing that continue to kill unarmed Black people. It includes the immense wealth disparity borne by Black American descendants, the cumulative legacy of our nation’s trajectory of racial injustice. Reparations is about repairing the wound, both acknowledging the moral failing and making restitution for lives robbed. Reparations ultimately aspires to the righting of a wronged relationship and the deep spiritual yearning for reconciliation. When asked “Why reparations?” several members of the BCST responded with these statements.

Unity Church has been on a 20-year journey to becoming an actively antiracist multicultural community. We continue to learn about the history of this country and its development and economic power built on the exploitation of African Americans and the appropriation of land from Native Americans. And we are aware of the current disparities in education, wealth, health and safety experienced by Black, Indigenous and People of Color that are an outgrowth of those foundational practices of exploitation.

The more we learn about the history of mistreatment of Black and Native Americans, and the continuing effect of that mistreatment into the present, the more it seems clear that some form of restitution must be made. Kevin Shird, in a recent column in the Pioneer Press, says compensation today for historic injustices would be a major step forward. However, beyond any monetary compensation, he stated that just the acknowledgement of the injustices committed against Black and Indigenous people matters. The need for reparations or restitution is clear. What gets complicated is how to do it and who is responsible. House Resolution H.R.- 40, named after the 40 acres and a mule promised to enslaved people after emancipation, but never given, is a bill seeking to establish a federal commission to examine the impacts of the legacy of slavery and recommend proposals to provide reparations. The bill does not authorize payments; it creates a commission to study the problem and recommend solutions. Representative John Conyers, Jr., of Michigan introduced the bill every year starting in 1989. After he retired in 2017 at age 88, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee, a Democrat from Texas, assumed the role of first sponsor of the bill. 2021 was the first year the bill made it out of committee. Locally, the St. Paul City Council established the Reparations Legislative Advisory Committee in June 2021 to lay the groundwork for the Saint Paul Recovery Act Community Reparations Commission. The Commission will develop recommendations to “specifically address the creation of generational wealth for the American Descendants of Chattel Slavery and to boost economic mobility and opportunity in the Black community.” The ordinance to create the reparations commission will be coming before the council yet this year, after which it will be Mayor Carter who appoints the commission members. It is hoped that he will do that after the first of the year. And the issue of broken treaties and restoring Native lands is a particular form of reparations that needs to be addressed. As members of the BCST seek to expand and deepen conversations about Unity’s role in reparations, watch for future articles that dig into these and other efforts addressing reparations and how this congregation might contribute. Available in Unity's Library The Color of Wealth: The Story Behind the U.S. Racial Wealth Divide Barbara Robles, Betsy Leondar-Wright, Rose Brewer, 2006 The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America Richard Rothstein, 2017 Available Online "The Case for Reparations," The Atlantic magazine, Ta-Nehisi Coates, 2014 Truth Telling and Healing: Indigenous and Environmental Justice Series Beloved Community Communications Team The “Honoring Water Protectors Discussion” held on December 1, 2021, in the Sanctuary at Unity Church and livestreamed on YouTube featured two remarkable water protectors: Sharon Day, executive director of The Indigenous People’s Task Force and leader of the Nibi Walk movement, and Tara Houska, an attorney, as well as environmental and Indigenous rights activist. Photographer John Kaul was inspired by the work of Indigenous and these two remarkable women. His work can be seen in the Eliot Wing photo and story exhibit, and he will post photos from the show on his Facebook page: www.facebook.com/john.kaul. We were inspired by the water protectors and their deep respect for the earth and wanted to share what they told us about how you can help. Ideas on How You Can Help from Tara Houska and Sharon Day:

Learn about the Honor the Earth organization. Tara Houska is the National Campaigns Director. Pull down the “Action” menu for how you can help. Reshape your relationship with nature. Think about how everything you consume comes from nature, that everything around us, including our bodies, is of the earth. Connect to the idea that water and the earth are not resources to be consumed but a living thing with spirit that is endangered in Minnesota. Contact Gov. Walz: Drop the charges against Line 3 activists. Minnesota Public Radio reported in September 2021 that nearly 900 people have been charged, most with misdemeanors but some with arbitrary and escalated felony and gross misdemeanor charges. Call Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and ask him to stop infringement on first amendment rights to peaceful assembly and to protest, and drop the charges against Line 3 activists: 651-201-3400, and/or tweet Gov. Walz: @GovTimWalz, #DropL3Charges Donate to the Line 3 Rapid Response Campaign. The Center for Protest Law & Litigation is administering a fund to subsidize and support legal costs for people arrested in opposition to the Line 3 pipeline. If you prefer to pay by mail, write a check with “CPPL/Line3” in the subject line and mail to: Partnership for Civil Justice Fund 617 Florida Ave, NW, Washington DC, 20001 Protect the Boundary Waters and water in Northern Minnesota from sulfide mining. For information on the legal case against PolyMet to prohibit this dangerous form of mining and to see what you can do, visit the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy. To stay abreast of the community outreach teams working on these issues at Unity Church:

|

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

March 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |