|

Erika Sanders, Beloved Community Communications Team A few months ago, Pauline Eichten brought an opening reading to a meeting of the Beloved Community Communications Team. Although written by Bishop Ken Untener in 1979, it’s often called the Oscar Romero prayer because it summarizes the ministry of Archbishop Romero.  This is what we are about: We plant seeds that one day will grow. We water seeds already planted, knowing that they hold future promise. We lay foundations that will need further development. We provide yeast that produces effects beyond our capabilities. We cannot do everything and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that. This enables us to do something, and to do it very well. It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning, a step along the way, an opportunity for God's grace to enter and do the rest. We may never see the end results, but that is the difference between the master builder and the worker. We are workers, not master builders, ministers, not messiahs. We are prophets of a future not our own. The members of our group were energized by the prayer, and by the reminder that we commit to the unknown potential of our work every time we take action to build Beloved Community.

We decided to share it with other Unity Church members and ask about their ability to continue their own antiracism work. How do they embrace the fact that it is work full of ambiguities with no set end-point? Molly Flattum, a Welcome Team member and Spirit Play teacher, and Linda Kjerland, a member of the Congregational Care Team, weighed in. Erika: When you read Romero’s prayer, how did its words resonate with you, and with your activities at Unity Church? Linda: The prayer says it all about keeping at it. I need to continue to prime the pump. As a younger child, I visited my grandparent's farm. Prominent in the yard was a tall rusting hand pump — it produced the first trickles of water only after some effort. I need to continually put yeast in my own dough. I need to listen and to befriend books that provoke, inform, and challenge me. Without repeated infusions, I can tuck in, miss calls for disturbance or misread my own emotions. Molly: The prayer reminds me of how, on the Welcome Team, we give great attention to how we have little snippets of conversation with congregants and visitors on Sundays, and how we try to infuse those small moments with meaning. How do those quick interactions create a space that is welcoming for everyone? What does that space look and feel like when it is engaging in antiracism, or welcoming people with disabilities or other marginalized identities? Erika: How do you grapple with the fact that this work has no point of completion or outcome? Molly: That really resonated with me as a Spirit Play teacher and a parent. As a parent, not having an end-point isn’t so scary, because we know that the work of growth is never-ending. Raising good humans is not about an end point, it is about ongoing action. It’s about raising kids to never be silent. My daughter is a preschooler, and is noticing differences like who has glasses and who doesn’t, and who uses a wheelchair and how they’ll enter a building. We’re normalizing conversations about difference and justice. Children hold me accountable. There’s always more work and learning to do. The idea of having an end goal would almost be limiting, because it might limit what you’re willing to do for the effort. Erika: In your Unity activities, do you find yourself employing the antidotes to white supremacy culture? Linda: I’d like to take time with each characteristic, putting them into intentional discussions within the Congregational Care team as we endeavor to reflect, rethink, and expand for whom and how we show up. My reading on antiracism, including at Unity, has pushed my willingness to see, feel, and heed the indicators of white supremacy culture. Erika: What does the use of the word “prophets” in the final line of the prayer mean to you? Do you see your work as prophetic? Molly: Prophet is a word that lands awkwardly for me. For me, it is more a question of: we are here so temporarily, how do we create a lasting impact? The work we do has to be the hard work, and it has to be part of our daily lives. As a parent, the fact that I’m doing advocacy and justice work–not just for my own sake, but for my children and the whole community — is what makes this holy work. Children help me stay anchored in the moment and keep asking the question, “What’s right in front of me?” It’s about Romero’s seed in the moment and the future.

0 Comments

Pauline Eichten, Beloved Community Communications Team I attended the February 22 Intersectionality 101 session led by Alfonso Wenker of Team Dynamics. He described it as a teach-in and began with a definition. Intersectionality is about the identities that intersect in ways that affect how individuals are viewed, understood and treated. Specifically, it’s the “simultaneous, overlapping and compounding nature of multiple forms of injustice and discrimination.” The oppression experienced can operate at the internal, interpersonal, institutional and structural level. The term was initiated by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 as a legal concept related to cases of discrimination. Judges seemed unable to see the overlapping gender and racial discrimination faced by black women, and looked at them as separate issues. Intersectionality provided a way to address the multiple layers of discrimination a person might be experiencing. Rinku Sen, in an essay about intersectionality, points out that it isn’t an identity, it’s a theory, a lens that can help us be more effective in our social justice approach. He wrote:

I was at a recent discussion about the criminal justice system and was struck by a comment from one of the presenters. He shared a definition of reconciliation that he learned in South Africa: reconciliation is removing barriers to authentic relationships. Might our tendency to oversimplify, and assume we know who someone is and what they experience, be one of those barriers? How can we use an intersectional lens to expand the possibilities in our encounters with each other? For more on this topic, see: The final Intersectionality 101 follow up session "Class and Race" will be held on March 14 at 6:30-8:30 p.m., in Parish Hall. Please register!

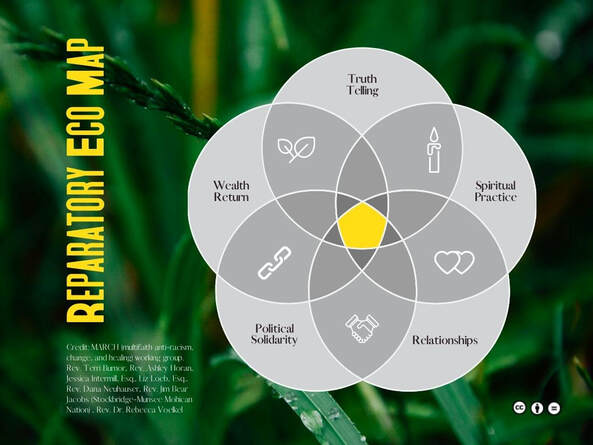

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team Session three of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light’s (MNIPL) Reparations Learning Table generated discussion and reflection around how our faith community traditions or spiritual practices determine how we engage in meaningful repair work for the long haul. Take a look at the MARCH/Multifaith Anti-Racism Change and Healing Eco Map as a visual reminder of our reparations journey. Reparatory Eco Map credit: MARCH (multifaith anti-racism, change, and healing) Rev. Terri Burnor; Rev. Ashley Horan; Jessica Intermill, Esq.; Liz Loeb, Esq.; Rev. Dana Neuhauser; Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation, Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voekel Learning about atrocities that our faith traditions committed against people of color may motivate us to abandon those communities. Yet, they can be the very place in which we find strength and support to engage in what Reparations Learning Table co-leader Jessica Intermill calls “the repentance/repair/return framework.”

This notion of lament, then repair and return of ill-gotten gains with penalty payment included, is a theme found in many faith traditions. The Biblical story of Zacchaeus the tax collector and Jesus (Luke 19:1-10 New International Version) is one of several examples. Aparigraha in the practice of yoga is the concept that nonpossession of things grounds you in the universe. Zen Buddhism teaches the ethics of not taking what is not given. Many Indigenous nations live by the code, “take only what you need.” It’s by no means a new concept. We’re just returning to it. The 7th Principle of Unitarian Universalism calls us to respect “the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” The proposed 8th principle currently under consideration by the Unitarian Universalist Association — “journeying toward spiritual wholeness by working to build a diverse multicultural Beloved Community by our actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions” — could be a call to lament, repair, and return land and resources to our Black and Indigenous neighbors. What does this action look like? And why do the work as a faith community? MNIPL Reparations Table co-leader Liz Loeb lifted up these reasons:

This is intergenerational work: elders possess wisdom that, when combined with the energy and new ideas of younger people, can create a stronger faith community committed to the spiritual practice of reparations, however they are defined. Here’s a personal example. I have an adopted, now estranged, Ojibwe brother who many in the Two Harbors, Minnesota, public education and law enforcement systems deemed lesser than the white kids, while growing up. When some believed that he could succeed, he did, but many teachers expected nothing from him. And that’s what they got. My brother wound up in juvenile detention for minor offenses. When he got out, the local sheriff typically went after him first when a crime occurred. I’m currently pursuing a master’s in divinity in UU Social Justice and completing my Community Pastoral Education (CPE) unit with Volunteers of America High School. There I provide whatever support staff needs to help mostly students of color who’ve been bounced out of the mainstream Minneapolis Public School system. My fellow Social Justice CPE cohort meets at Stillwater State Prison because that’s where half of our group lives. We are each trying to make the lives better for those who, for whatever reason, veered off the path to a healthy life. We are trying to return what was taken from the ancestors of our clients. I work with kids who have family members in prison, who are from immigrant families struggling to make their way in a completely foreign country, who’ve already been to juvenile detention, and/or who are members of gangs. Some will graduate. Some won’t. I could not do any of this work as an individual. Getting involved in Unity’s social justice work led me to pursue a master’s in divinity in UU Social Justice so that I may work in community to repent, repair, and return that which was ill-gotten. As Dr. Maya Angelou said, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better!” I leave you with prompts for reflection: What traditions or practices help ground you when you think about reparations as a lifelong commitment? What insight does your faith tradition or community of practice hold that feels relevant to reparations? For more information about reparations work, please visit these online resources: Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light Reparation actions from around the country Amicus Volunteers of America The Justice Database, a project of Unity Church |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

May 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |