|

Suki Sun, Beloved Community News Guest Writer, and Shelley Butler, Beloved Community News Team

Sometimes two but more often four to five people make a commitment to read, listen, or view a resource vetted by a small committee at Unity dedicated to expanding the understanding of racism for the purpose of dismantling it. The pairs or groups gather over two-three months and then come to a larger meeting to report what surprised them about what they learned, what questions arose, and what they are called to do next. This is the Unity Church Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) program, which arose out of Justice for George/Next Right Action discussions in the summer of 2020. Suki Sun is a participant in the program with a story to tell. She was born in Shanghai, China, and lived in Manhattan for ten years before moving to Minnesota two years ago. She has been involved in two ALP groups this year, and in that short time has impressed us with her dedication to the program and her wisdom. Suki’s Story Being a person of color myself doesn’t automatically make me immune from racial bias — this is the biggest lesson I have learned since joining the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners program. I learned that the hard way during a conversation at Recovery Cafe Frogtown with a recovery coach and motivational speaker who is a middle-aged African American gentleman. I mentioned to him that since I got sober, I picked up the violin again after a 30-year pause and recently joined an orchestra in Saint Paul. “Which orchestra?” I could see his interest twinkling in his eyes. “East Metro Symphony Orchestra and it used to be called 3M Symphony Orchestra,” I replied. “Oh! 3M Symphony!” Now his eyes were totally lit up, “I had been to many of their concerts before they changed the name. What a great orchestra you have joined! Congratulations!” On top of the excitement whenever I meet someone who enjoys classical music, I also noticed that this time, it included a tone of uneasy surprise, or I could even call it a mind shock based on his race; he was the first African American I ever talked with about classical music. I was struggling with some racing thoughts. I wanted to tell him how unique it was for me to talk with an African American who supports live classical music concerts, which was a fact to me, but sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. I also wanted to mention that I wish there were more African American musicians in our orchestra (we have zero), which was also a fact to me but also sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. And the loudest question echoing in my mind at that moment was, “Why do you think we don’t see more African Americans in the classical music scene?“ And of course, I didn’t say that either. My racial bias acted like an automatic yet dysfunctional machine, vacuuming the air from my mind, suffocating the natural flow of an otherwise delightful chat about classical music, one of my favorite topics. In the end, I didn’t have the mental capacity to extend and deepen our conversation about classical music by asking him, “Who are your favorite composers and conductors? What is your favorite piece? Do you play any instruments?” In the end, I was the one hurt by my racial bias because I ruined the chance to connect with another person in a more profound and meaningful way. After all, in recovery connection is the opposite of addiction. I also lost the opportunity to hear more details of his story as an avid classical music supporter to uproot my bias. New wisdom always plants more healthy seeds when we learn from a powerful story instead of abstract statements. But I didn’t value the personal stories from BIPOC as a tool to wither my racial bias until I was in the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) group this spring. In an intimate setting of five members, we listened to ten episodes of the podcast “The Sum of Us,” which included personal stories from Memphis to Orlando, from Kansas City to Manhattan Beach, California; and then met weekly to digest these stories. During our meetings, I find that as long as I keep my eyes and mind open, even just one person's story is powerful enough to change my years-long, or even decades-long wrong assumptions. That’s why I am so grateful to be part of the Antiracism Literacy Partners. Small group, small steps, but big potential. Evolution always will feel charming. Note: The League of American Orchestras, in “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Diversity in the Orchestra Field in 2023,” reports that while the U.S. Population of Blacks is 12.6%, the percentage of Black people in orchestra is only 2.4%. Read the report for their analysis and recommendations for correcting the inequities. Anyone can join Unity's Antiracism Literacy Partners program. Questions? Contact Becky Gonzalez-Campoy at beckygc83@gmail.com.

0 Comments

By Shelley Butler, Beloved Community Communications Team, and Laura Park, Beloved Community Staff Team Someone said to me once that for them, ironing was practically a spiritual practice; they were kidding (I think). I get it — there is a misconception that anything can be a UU spiritual practice because our faith does not dictate these to us. We aren’t encouraged to pray five times each day facing the Kaaba at Mecca, nor do we perform baptisms or partake in the Eucharist — all meaningful practices in other religions.

Yet, spiritual practice is one of the cornerstones of living our faith at Unity Church. Our second end statement says that we “ground ourselves in personal practice and communal worship that grows our capacity for wonder and spiritual deepening.” Consider this, attributed to Buddha, “There are only two mistakes one can make along the road to truth: Not going all the way, and not starting.” So, what are spiritual practices? What form do they take? Are there more types of spiritual practice than prayer, meditation, and worship? How do I create my own spiritual practice? What makes a spiritual practice different from simply providing comfort, or from Marx’s idea of religion as “the opium of the people”? How do we incorporate spiritual practice into our lives? In September, you’ll have the opportunity to explore the answers to these questions and take the mystery out of spiritual practice in a three-part series, “Spiritual Practice: Discovery and Transformation.” Unity Minister of Faith Formation Rev. KP Hong, Director of Membership and Hospitality Laura Park, and Beloved Community Staff Team member Angela Wilcox will lead the series, with help from other presenters such as Rev. Kathleen Rolenz. Save the dates: Wellspring Wednesdays, September 13, 20, and 27, at 7:10 p.m. Session one on September 13 is about the what, the why, and the how of spiritual practice. Session two will be experiential as participants “try on” various practices and reflect on the meaning of them. The third session on September 27 will connect spiritual practice and antiracist multiculturalism, exploring how they intertwine and inform our daily lives and social justice work. Then, come back for a follow-up session in February to check in on our spiritual practices. So, whether an aspiration or something already embedded in your life, don’t miss this opportunity to take a deeper dive into spiritual practice. In the meantime, we leave you with these prompts for reflection: Which spiritual practices are meaningful to you? Are you open to greater discovery and transformation through spiritual practice? For more information about the series, check the September 2023 commUNITY newsletter and the church website. To find out more about Unitarian Universalism and spiritual practice, see:

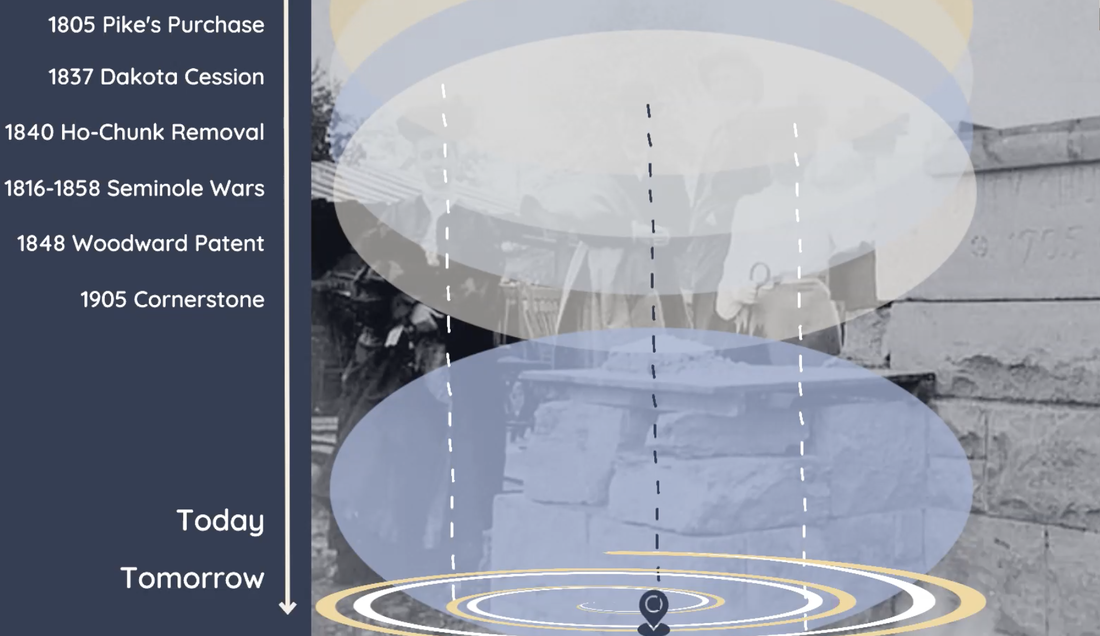

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications and Indigenous Justice Ministry Teams Unity Church-Unitarian sits on land stolen from the Dakota people. We read this in our weekly Order of Service and proclaim it prior to the start of most church meetings, our own pledge of allegiance of sorts. However, what does this really mean and how did it happen? Unity’s Act for the Earth and Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Ministry Teams series, “Truth Telling and Healing: Indigenous and Environmental Justice," included a close look at how Unity came to be located on Dakota land (Land and Reparations). During this presentation in March 2023, Jessica Intermill of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light and Intermill Land History Consulting, invited us to look at history differently. Unity Church-Unitarian sits on land stolen from the Dakota people. We read this in our weekly Order of Service and proclaim it prior to the start of most church meetings, our own pledge of allegiance of sorts. However, what does this really mean and how did it happen? Unity’s Act for the Earth and Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Ministry Teams series, “Truth Telling and Healing: Indigenous and Environmental Justice," included a close look at how Unity came to be located on Dakota land (Land and Reparations). During this presentation in March 2023, Jessica Intermill of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light and Intermill Land History Consulting, invited us to look at history differently. History is typically laid out chronologically in books: American Revolution, Slavery, Western Expansion, and the Civil War. However, slavery occurred before and during the Revolution and played a part in westward expansion. “Today’s physical landscape has everything that came before us right now,” explained Intermill. The question is, “What does it mean to take responsibility for a past that’s not past?” Intermill mapped the location of Unity Church and then peeled back the layers of events on our land since the occupation of stolen Dakota land. She started with the arrival of United States General Zebulon Pike at the convergence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers who declared it an ideal spot to build a fort (Fort Snelling). In 1805, the United States Congress purchased from the Dakota people 155,000 acres of land at this spot for practically nothing. Through deception and manufactured devaluation, land that should have brought $300,000 to the Dakota people possibly brought them the remains of $2,000 worth of goods. Keep in mind that Bdote, the convergence of these two rivers, is where human life began according to the Dakota. So, this is sacred land which started out as a place of genesis and eventually became the site of genocide. Things didn’t fare any better when the U.S. government purchased more land surrounding Fort Snelling through the 1837 Sioux Treaty. Here again, treacherous cruelty prevailed — this time the Dakota only received $16,000 through this treaty while those who had intermarried with them received $110,000, and $90,000 covered fabricated Dakota debt created by white people (many of whom were of the federal government). This thievery stemmed from the demise of the fur trade and a need for those traders to come up with a new source of income. From there, the U.S. government paid soldier Sam Taylor for his work with a New York regiment with a voucher for a section of land between St. Clair and Marshall Avenues. Taylor didn’t want the land and sold it to land speculators, and it eventually wound up in the possession of a man named Woodword. So, back to Intermill’s original question: “What does it mean to take responsibility for the past that’s not past?” Participants in the final session in the Truth Telling and Healing series held last month shared their stories of how the programs had impacted them. These are some of the themes that emerged:

The group then considered next steps for themselves as individuals and for Unity as a congregation:

Among the suggested resources to continue the Indigenous and environmental justice journey is the Native Governance Center's Beyond Land Acknowledgment Guide. This is one avenue Unity’s Indigenous Justice Community Outreach Team will explore as it plans future learning and spiritual growth opportunities. Be sure to also check out Act for the Earth activities. Meanwhile, continue your own spiritual and educational journey by exploring: |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

April 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |