|

Suki Sun, Beloved Community News Guest Writer, and Shelley Butler, Beloved Community News Team

Sometimes two but more often four to five people make a commitment to read, listen, or view a resource vetted by a small committee at Unity dedicated to expanding the understanding of racism for the purpose of dismantling it. The pairs or groups gather over two-three months and then come to a larger meeting to report what surprised them about what they learned, what questions arose, and what they are called to do next. This is the Unity Church Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) program, which arose out of Justice for George/Next Right Action discussions in the summer of 2020. Suki Sun is a participant in the program with a story to tell. She was born in Shanghai, China, and lived in Manhattan for ten years before moving to Minnesota two years ago. She has been involved in two ALP groups this year, and in that short time has impressed us with her dedication to the program and her wisdom. Suki’s Story Being a person of color myself doesn’t automatically make me immune from racial bias — this is the biggest lesson I have learned since joining the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners program. I learned that the hard way during a conversation at Recovery Cafe Frogtown with a recovery coach and motivational speaker who is a middle-aged African American gentleman. I mentioned to him that since I got sober, I picked up the violin again after a 30-year pause and recently joined an orchestra in Saint Paul. “Which orchestra?” I could see his interest twinkling in his eyes. “East Metro Symphony Orchestra and it used to be called 3M Symphony Orchestra,” I replied. “Oh! 3M Symphony!” Now his eyes were totally lit up, “I had been to many of their concerts before they changed the name. What a great orchestra you have joined! Congratulations!” On top of the excitement whenever I meet someone who enjoys classical music, I also noticed that this time, it included a tone of uneasy surprise, or I could even call it a mind shock based on his race; he was the first African American I ever talked with about classical music. I was struggling with some racing thoughts. I wanted to tell him how unique it was for me to talk with an African American who supports live classical music concerts, which was a fact to me, but sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. I also wanted to mention that I wish there were more African American musicians in our orchestra (we have zero), which was also a fact to me but also sounded wrong, so I didn’t say it. And the loudest question echoing in my mind at that moment was, “Why do you think we don’t see more African Americans in the classical music scene?“ And of course, I didn’t say that either. My racial bias acted like an automatic yet dysfunctional machine, vacuuming the air from my mind, suffocating the natural flow of an otherwise delightful chat about classical music, one of my favorite topics. In the end, I didn’t have the mental capacity to extend and deepen our conversation about classical music by asking him, “Who are your favorite composers and conductors? What is your favorite piece? Do you play any instruments?” In the end, I was the one hurt by my racial bias because I ruined the chance to connect with another person in a more profound and meaningful way. After all, in recovery connection is the opposite of addiction. I also lost the opportunity to hear more details of his story as an avid classical music supporter to uproot my bias. New wisdom always plants more healthy seeds when we learn from a powerful story instead of abstract statements. But I didn’t value the personal stories from BIPOC as a tool to wither my racial bias until I was in the Unity Antiracism Literacy Partners (ALP) group this spring. In an intimate setting of five members, we listened to ten episodes of the podcast “The Sum of Us,” which included personal stories from Memphis to Orlando, from Kansas City to Manhattan Beach, California; and then met weekly to digest these stories. During our meetings, I find that as long as I keep my eyes and mind open, even just one person's story is powerful enough to change my years-long, or even decades-long wrong assumptions. That’s why I am so grateful to be part of the Antiracism Literacy Partners. Small group, small steps, but big potential. Evolution always will feel charming. Note: The League of American Orchestras, in “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Diversity in the Orchestra Field in 2023,” reports that while the U.S. Population of Blacks is 12.6%, the percentage of Black people in orchestra is only 2.4%. Read the report for their analysis and recommendations for correcting the inequities. Anyone can join Unity's Antiracism Literacy Partners program. Questions? Contact Becky Gonzalez-Campoy at beckygc83@gmail.com.

0 Comments

By Shelley Butler, Beloved Community Communications Team, and Laura Park, Beloved Community Staff Team Someone said to me once that for them, ironing was practically a spiritual practice; they were kidding (I think). I get it — there is a misconception that anything can be a UU spiritual practice because our faith does not dictate these to us. We aren’t encouraged to pray five times each day facing the Kaaba at Mecca, nor do we perform baptisms or partake in the Eucharist — all meaningful practices in other religions.

Yet, spiritual practice is one of the cornerstones of living our faith at Unity Church. Our second end statement says that we “ground ourselves in personal practice and communal worship that grows our capacity for wonder and spiritual deepening.” Consider this, attributed to Buddha, “There are only two mistakes one can make along the road to truth: Not going all the way, and not starting.” So, what are spiritual practices? What form do they take? Are there more types of spiritual practice than prayer, meditation, and worship? How do I create my own spiritual practice? What makes a spiritual practice different from simply providing comfort, or from Marx’s idea of religion as “the opium of the people”? How do we incorporate spiritual practice into our lives? In September, you’ll have the opportunity to explore the answers to these questions and take the mystery out of spiritual practice in a three-part series, “Spiritual Practice: Discovery and Transformation.” Unity Minister of Faith Formation Rev. KP Hong, Director of Membership and Hospitality Laura Park, and Beloved Community Staff Team member Angela Wilcox will lead the series, with help from other presenters such as Rev. Kathleen Rolenz. Save the dates: Wellspring Wednesdays, September 13, 20, and 27, at 7:10 p.m. Session one on September 13 is about the what, the why, and the how of spiritual practice. Session two will be experiential as participants “try on” various practices and reflect on the meaning of them. The third session on September 27 will connect spiritual practice and antiracist multiculturalism, exploring how they intertwine and inform our daily lives and social justice work. Then, come back for a follow-up session in February to check in on our spiritual practices. So, whether an aspiration or something already embedded in your life, don’t miss this opportunity to take a deeper dive into spiritual practice. In the meantime, we leave you with these prompts for reflection: Which spiritual practices are meaningful to you? Are you open to greater discovery and transformation through spiritual practice? For more information about the series, check the September 2023 commUNITY newsletter and the church website. To find out more about Unitarian Universalism and spiritual practice, see:

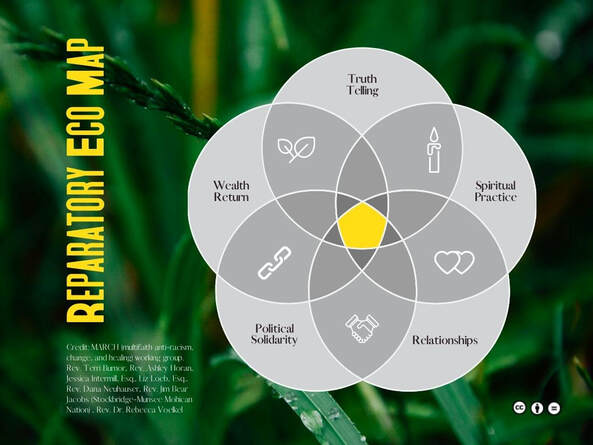

Rebecca Gonzalez-Campoy, Beloved Community Communications Team Session three of Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light’s (MNIPL) Reparations Learning Table generated discussion and reflection around how our faith community traditions or spiritual practices determine how we engage in meaningful repair work for the long haul. Take a look at the MARCH/Multifaith Anti-Racism Change and Healing Eco Map as a visual reminder of our reparations journey. Reparatory Eco Map credit: MARCH (multifaith anti-racism, change, and healing) Rev. Terri Burnor; Rev. Ashley Horan; Jessica Intermill, Esq.; Liz Loeb, Esq.; Rev. Dana Neuhauser; Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs (Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation, Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voekel Learning about atrocities that our faith traditions committed against people of color may motivate us to abandon those communities. Yet, they can be the very place in which we find strength and support to engage in what Reparations Learning Table co-leader Jessica Intermill calls “the repentance/repair/return framework.”

This notion of lament, then repair and return of ill-gotten gains with penalty payment included, is a theme found in many faith traditions. The Biblical story of Zacchaeus the tax collector and Jesus (Luke 19:1-10 New International Version) is one of several examples. Aparigraha in the practice of yoga is the concept that nonpossession of things grounds you in the universe. Zen Buddhism teaches the ethics of not taking what is not given. Many Indigenous nations live by the code, “take only what you need.” It’s by no means a new concept. We’re just returning to it. The 7th Principle of Unitarian Universalism calls us to respect “the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” The proposed 8th principle currently under consideration by the Unitarian Universalist Association — “journeying toward spiritual wholeness by working to build a diverse multicultural Beloved Community by our actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions” — could be a call to lament, repair, and return land and resources to our Black and Indigenous neighbors. What does this action look like? And why do the work as a faith community? MNIPL Reparations Table co-leader Liz Loeb lifted up these reasons:

This is intergenerational work: elders possess wisdom that, when combined with the energy and new ideas of younger people, can create a stronger faith community committed to the spiritual practice of reparations, however they are defined. Here’s a personal example. I have an adopted, now estranged, Ojibwe brother who many in the Two Harbors, Minnesota, public education and law enforcement systems deemed lesser than the white kids, while growing up. When some believed that he could succeed, he did, but many teachers expected nothing from him. And that’s what they got. My brother wound up in juvenile detention for minor offenses. When he got out, the local sheriff typically went after him first when a crime occurred. I’m currently pursuing a master’s in divinity in UU Social Justice and completing my Community Pastoral Education (CPE) unit with Volunteers of America High School. There I provide whatever support staff needs to help mostly students of color who’ve been bounced out of the mainstream Minneapolis Public School system. My fellow Social Justice CPE cohort meets at Stillwater State Prison because that’s where half of our group lives. We are each trying to make the lives better for those who, for whatever reason, veered off the path to a healthy life. We are trying to return what was taken from the ancestors of our clients. I work with kids who have family members in prison, who are from immigrant families struggling to make their way in a completely foreign country, who’ve already been to juvenile detention, and/or who are members of gangs. Some will graduate. Some won’t. I could not do any of this work as an individual. Getting involved in Unity’s social justice work led me to pursue a master’s in divinity in UU Social Justice so that I may work in community to repent, repair, and return that which was ill-gotten. As Dr. Maya Angelou said, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better!” I leave you with prompts for reflection: What traditions or practices help ground you when you think about reparations as a lifelong commitment? What insight does your faith tradition or community of practice hold that feels relevant to reparations? For more information about reparations work, please visit these online resources: Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light Reparation actions from around the country Amicus Volunteers of America The Justice Database, a project of Unity Church |

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

March 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |