Wellspring Wednesday presentation, January 28, 2020 By Merrill Aldrich, Unity Church Member Tracing the genesis and the effects of structural racism can be arduous and labor intensive work. Recently, Kirsten Delegard, director of the Mapping Prejudice Project at the University of Minnesota shared with us a glimpse of the data, visualizations, painstaking research and personal anecdotes that she and her colleagues have combined to tell the sad history of racial covenants in the Twin Cities. Racial covenants were real estate contracts -- clauses inserted into warranty deeds--used by real estate developers and agents to enforce unlawful segregation and prevent people of color from buying or occupying property. With geographic maps, showing specific blocks and years, the Mapping Prejudice project details the areas of Hennepin County where segregation was reinforced by these clauses in property deeds that reserved land and structures for white people. The maps are backed by exhaustive research into the title history of lots where phrases prohibited the sale, using a variety of terms, to non-whites. Delegard’s personal interest in this subject came from several generations of her family living in Minneapolis, and a discomfort with what she described as “the dissonance” she observed in the lore of her home town. A certain set of mythologies we have in the twin cities about civic virtue, with stories like Hubert Humphrey’s efforts to end racial segregation and Walter Mondale’s Fair Housing Act, while true, seemed to her to obscure other narratives that are explicitly racist and should be told. She “resolved to lead my home town through a process of remembering” by reconstructing the history of racial covenants and their effect in creating de facto segregation in Minneapolis. If you missed this talk, much of the content is available in the film Jim Crow of the North, available to stream online. Volunteer Opportunity Because of the nature of the source data for the Hennepin County mapping project, a large contingent of crowd-sourced volunteers came together to review the historical deed documents. Almost 3,000 volunteers read about 177,000 deed-related documents to compile the data. Coming up in a few weeks -- specific date TBD -- the project will formally expand to enable volunteers to gather this data for Ramsey County, including Saint Paul. We’d like to encourage anyone at Unity with an interest in this work to pitch in and assist in expanding the map. To find out more, sign up to receive the Mapping Prejudice Project electronic newsletter (scroll to the bottom of the page and locate the "Stay connected with Mapping Prejudice" box).

1 Comment

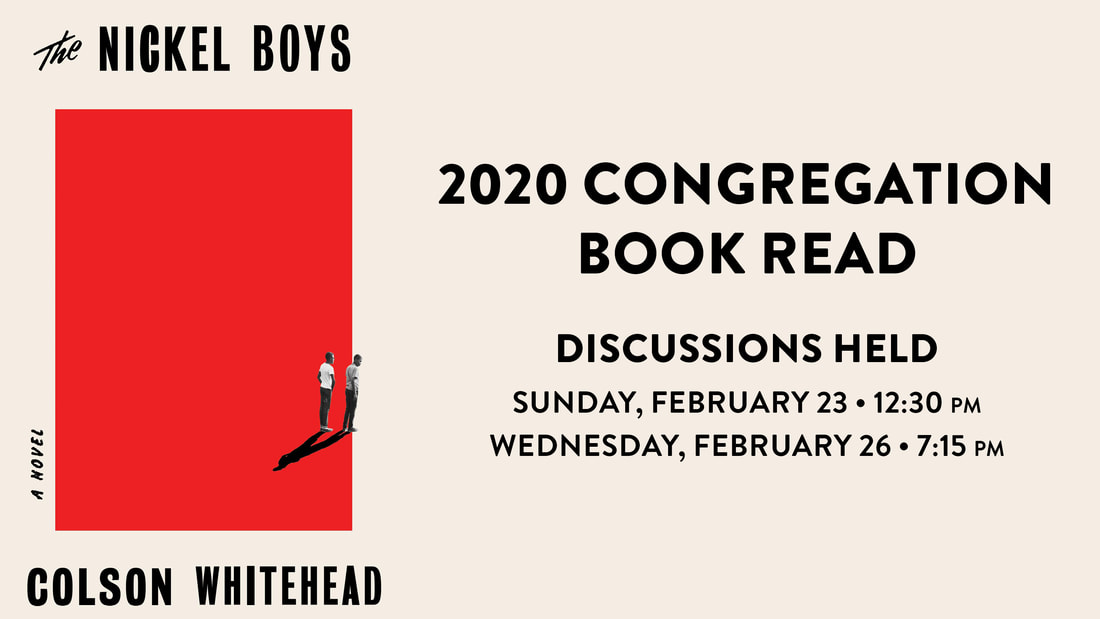

By Merrill Aldrich, Unity Church Member Each Sunday our worship at Unity Church opens with a reference to “the Beloved Community we seek to make real.” With Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, birthday just past, I have been trying to further educate myself about this term and this work that so many people and organizations continue since King’s death. “Beloved Community” has historical roots, an interpretation that Dr. King extended and popularized, and, I have learned, a history within our own institution since at least 2005, and within the UUA. From both religious and philosophical threads, Dr. King shaped the idea of “Beloved Community” throughout his life into a clear vision that people could actively work toward. He prompted us to work to create a society that embodies principles and practices of mutual respect, support, integration, difference, nonviolence, and economic equality. King insisted that this goal was for this world, not the next, and we could work together toward creating it, here and now. At Unity Church, Beloved Community was invoked as an official term in 2005, when the board of trustees reframed “moral ownership,” one of the institution’s policies as follows: Policy D: Moral Ownership “The moral owners of Unity Church-Unitarian are those who yearn for the Beloved Community and see Unity Church as an instrument for its realization. The Beloved Community is engaged in the work of the spirit. It is community at the highest level of reality and possibility, where love and justice prevail.” This reference connects directly to Dr. King’s work stretching all the way back to 1957: “In 1957, writing in the newsletter of the newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference, [King] described the purpose and goal of that organization as follows: ‘The ultimate aim of SCLC is to foster and create the ‘beloved community’ in America where brotherhood is a reality... Our ultimate goal is genuine intergroup and interpersonal living — integration.’" (Smith/Zepp, Religion Online) Scholars of King’s work have tried to trace whether the term goes back even further. Several have pointed to the work of Josiah Royce (1855–1916), professor of history of philosophy at Harvard in the 1890s (The Problem of Christianity), or to King’s early advisor at Boston University, Edgar Brightman (1884–1953) (Moral Laws). For me, a very insightful description comes from an analysis by Gary Herstein in a 2009 article “The Roycean Roots of the Beloved Community:” “King’s notion of the Beloved Community rotates around two principal axes: the Beloved Community as the embodiment of agapic love and the Beloved Community as the embodiment of the Moral Laws.” (Herstein 91-107) Agapic Love, from the word “agape” (ah GAH pay) refers to the idea that we do or should share a common affection among all people, a fundamental love for our fellow human beings that underpins all our relationships. Moral Law describes how all of us as a matter of personal conscience should have a sense of right and wrong that transcends the written laws formally enacted in our communities, and should work to bring those written laws into congruence with moral law. Together these concepts — aspiration to a true or universal moral law, but based on common human love and compassion — enable us to do immediate, pragmatic work toward a society of justice, acceptance, nonviolence, and mutual affection. This might seem very abstract. What does it mean for our church community? For me, there are several important messages here. An example like the marriage equality action in the past ten years is illuminating when viewed through this lens: it was a change founded on increasing the mutual respect and affection between people (agape), perceiving and understanding that some among us were being mistreated. It required that we work to realign our formal / written laws with a more correct understanding about what fairness and justice would mean for more members of our society (moral law). Some of that work caused friction and made people uncomfortable. Both of these things require integrity, which for me reaches beyond a comfortable “holding of correct moral perceptions,” and even kindness, into a call to act on those perceptions. Coming back to Unity Church, I think the use of this term helps us in a number of ways. First, it’s picking up a movement in progress, refined by thought and energy over some eighty years. Second, though it might require a bit of explanation like this post, it gives us a clear frame of reference for the kind of community we want to form and the changes we want to see happen in the world. It enables the church to align with other organizations that share this same vision. Finally, it’s a call to action, to act with integrity, by examining our current relationships, envisioning the relationships we would like to have, and most importantly moving things toward that vision. I see this idea woven into the current Ends Statements and the Executive Team’s interpretation of End #1, “Create a multicultural spiritual home built on authentic relationships.” Executive Team Interpretation: “The Beloved Community is inherently multicultural and always aspirational. We begin this work with deep humility, acknowledging that we need help navigating what, for us, is uncharted territory. Authentic relationships begin when we recognize and root out our assumptions and deepen through active curiosity and growing friendship. This work asks us to confront systems of oppression, disrupt white privilege and fragility, build bridges across differences, and embrace an ever-growing repertoire in every dimension of our ministry. We promise to stay engaged despite discomfort and inevitable failures." (2020 Unity Church Annual Report 4-11) I have less direct personal experience with the national landscape of UU communities and with the UUA, but I can see that many congregations have picked up the work of Beloved Community. I have also been learning about the work started by Paula Cole Jones and Bruce Pollack-Johnson, and others, proposing an 8th UU Principle which directly invokes this concept and this work. The 8th principle has already been endorsed by Black Lives of Unitarian Universalism (BLUU) and Diverse Revolutionary UU Ministries (DRUUMM) and reads: “We, the member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association, covenant to affirm and promote: journeying toward spiritual wholeness by working to build a diverse multicultural Beloved Community by our actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions.” Though I have a lot to learn, it’s heartening to see us as an organization connect to this ongoing movement, both to learn from it and to put our energy and resources behind this common aspiration. Based on the true story of the hellish Dozier reform school that operated from 1900-2011, The Nickel Boys chronicles the experience of two Black boys sentenced there (one mistakenly) in the 1960s. The tension between one boy’s ideals, adopted from Martin Luther King, and the other’s skepticism leads to a decision that will echo down the decades. A story of the past that is still making news and has parallels to events today. Written by “America’s Storyteller,” as named by Time Magazine. One of Time Magazine’s 10 Best Fiction Books of the Decade, winner of the Kirkus Prize, and longlisted for the 2019 National Book Award. Discussions held Sunday, February 23, at 12:30 p.m., and Wednesday, February 26, at 7:15 p.m.

|

Topics

All

Beloved Community ResourcesUnity Justice Database

Team Dynamics House of Intersectionality Anti-Racism Resources in the Unity Libraries Collection Creative Writers of Color in Unity Libraries The History of Race Relations and Unity Church, 1850-2005 Archives

March 2024

Beloved Community Staff TeamThe Beloved Community Staff Team (BCST) strengthens and coordinates Unity’s antiracism and multicultural work, and provides opportunities for congregants and the church to grow into greater intercultural competency. We help the congregation ground itself in the understanding of antiracism and multiculturalism as a core part of faith formation. We support Unity’s efforts to expand our collective capacity to imagine and build the Beloved Community. Here, we share the stories of this journey — the struggles, the questions, and the collaborations — both at Unity and in the wider world.

The current members of the Beloved Community Staff Team include Rev. Kathleen Rolenz, Rev. KP Hong, Rev. Lara Cowtan, Barbara Hubbard, Drew Danielson, Laura Park, Lia Rivamonte and Angela Wilcox. |